Popular Italian ‘atmospheric’ composer Ludovico Einaudi stretches his wings with a full-scale opera, exploring the many and tragic dimensions of the refugee crisis which has engulfed Europe in the last decade. It’s a triumph; emotionally engaging, dramatically compelling and cathartic.

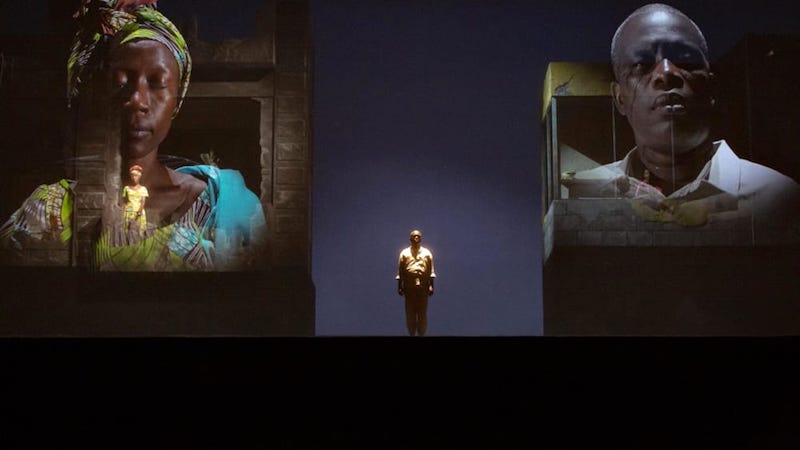

As the auditorium lights go down, the soft but driving pulse of Einaudi’s music rises from the pit. It’s an evocation of the sea, entirely familiar in style and content to fans of this most popular of contemporary composers, the most downloaded artists of all time in the field of classical streaming. The stage lights come up slowly, revealing a character suspended high above the stage, bobbing up and down. A video projection of the sea emerges, placing the bobbing man above and sometimes below the waves of the Mediterranean. It’s a captivating coup de theatre, telling us at once that Winter Journey is going to be much, much more than an ephemeral or lightweight musical experience – two of the adjectives which Einaudi’s detractors use to describe his music.

Winter Journey. All photographs © Rosellina Garbo

Winter Journey. All photographs © Rosellina Garbo

Palermo and Naples, Italy’s southern capitals, have borne much of the brunt of refugees who continue to risk their lives crossing the sea from Africa to Europe in search of stability and a better future (the morning after the performance reviewed here, Sky News told of another refugee boat which had foundered off the coast of Pantelleria, a small Italian island, with two drowned and 50 rescued). So it is fitting that Palermo’s Teatro Massimo and Naples’ Teatro di San Carlo have jointly commissioned this new work from Einaudi and acclaimed Irish writer Colm Tóibín. Winter Journey opened in Palermo on October 4. Limelight was there for the third performance.

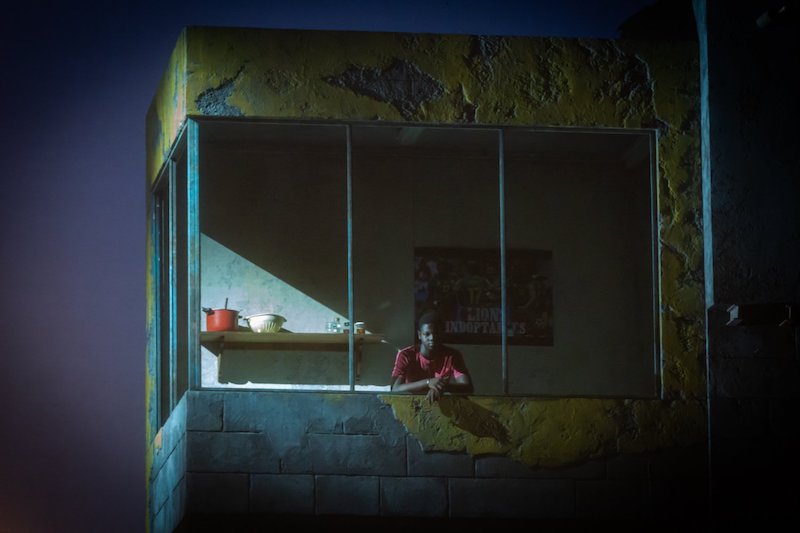

The story told is a simple one, familiar to anyone who has paid any attention whatsoever to the difficult choices faced by refugees. A man (played by Badara Seck from Senegal) decides to leave his war-torn country for a better life in Europe, leaving behind a woman (Rokia Traoré from Mali) and a male child (sung by Ghana-born Palermo resident Leslie Nsiah Afriyie and played on stage by Mouhamadou Sazll). At first the woman hears nothing, fearing that the man has drowned at sea. Intermittent text messages between the two convey desperation, relief and hope that things just might get better. As the man travels north to Germany, the European winter begins. At the same time the civil war in the country he left behind worsens, leaving the woman and the child in an increasingly desperate situation as power, water and phone networks disappear one by one. This is a winter journey in many senses. Scenes involving these three characters alternate with speeches by western political leaders (powerfully portrayed by Jonathan Moore) either pleading for sympathy or excoriating refugees for daring to cross borders. A Greek chorus chants repeats key phrases, such as “This is Europe’s cry”, or repeat the phrases of political leaders or the refugees.

The story allows plenty of opportunity for Einaudi to bring his wonderfully evocative music to a range of dramatic situations, exploring the characters’ individual emotional journey, the official discourse of politicians, and reactions of the crowd and the stages of the physical journey itself across sea and land, from warmth to cold.

Most of Einaudi’s works to date have been written for solo piano or small ensembles, so it was a delight to hear him working with a full-size orchestra, chorus, speakers and soloists. The orchestra of the Teatro Massimo, under the confident leadership of Carlo Tenan, provided a fresh and dramatic instrumental texture to underpin the stage action and drive the narrative. None of the soloists are trained opera singers. Much of the time the solo vocal lines are chanted or make use of traditional African melodies and musical styles (something that Einaudi studied under Luciano Berio when at the Giuseppe Verdi Music Conservatory in Milan). The blending of Einaudi’s hypnotic orchestral line, with the chants of the chorus and the African soloists was both exotic and riveting.

The musical layering provided by Einaudi continued seamlessly to Gianni Carluccio’s sets and lighting, and to the stage direction by Roberto Andò. The woman and child occupied boxes sitting above the stage, separating them from the ‘European’ world of the chorus and politicians on stage and suggesting a kind of imprisonment in their circumstances. The man, the refugee, quite literally floats in and out of these spaces. Video projections of the sea and winter landscapes complete the visual layering. The fact that the piece was conceived from the outset to incorporate video and that Einaudi’s music so powerfully conjures up visual images, made the video element of the staging entirely satisfactory and so much less perfunctory that the current fashion for video in opera theatres around the world.

This leaves the libretto. It is impossible to underestimate how much Tóibín’s poignant, poetic mastery of English contributed to the success of this venture. The desperation of the characters, the fierceness of political discourse surrounding refugees and the confused reactions of ordinary people were all brilliantly captured in a spare, direct libretto that fitted seamlessly with Einaudi’s score.

Such a combination of creative talents comes together rarely, and it was a great privilege to witness the birth of a work than will doubtless begin appearing in festivals and in opera theatres around the world in the years ahead. Watch out Glyndebourne, The Met, Adelaide.

Was this opera? Absolutely. Should we treat Einaudi as a serious composer? Definitely.

Ludovico Einaudi will tour Australia in 2020

Comments

Log in to join the conversation.