The reinvention of Two Feet, Meryl Tankard’s legendary work for solo dancer, opens with black curtains revealing the starkly-lit figure of a carnival doll on a music box. Although the music and role is from Giselle, it’s also a chilly reminder of Dr Coppelius’s life-size dancing doll, slowly spinning to the disembodied “plink-plink-plink” of a music box.

It’s a clue to the reality that ballet seems to be the natural home of Svengali relationships, whether fictional (Coppélia) or forged in the blisters, blood and tears of young dancers whose teachers demand… everything.

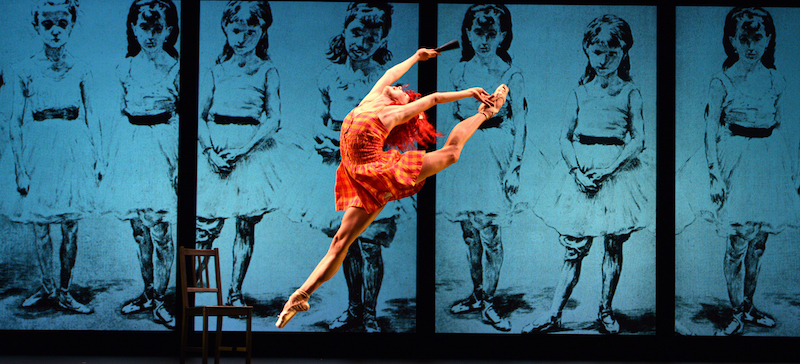

Natalia Osipova in Two Feet. Photograph © Regis Lansac

That demand also goes both ways: Two Feet is partially an homage to Olga Spessivtzeva, the great Russian romantic ballerina of the first part of the 20th century. Her brilliant career began to founder on a tour of Australia when her health – physical and mental – visibly faltered. She was eventually overwhelmed by her quest for perfection and lived out her days in an asylum in the US.

Spessivtzeva’s story is at the extreme end of what every dancer knows and endures: the physical discipline and often inhuman endurance required to make every movement look absolutely effortless. And the effort is not simply of the body. Two Feet could not have been made if young Tankard – already successful but dissatisfied with the constraints and parochialism of Australia – seemingly threw it all away to reinvent her dance life and mind in Europe with the Pina Bausch company.

Now, a dance generation on from Tankard’s own virtuoso performances of the piece, dating from 1988, there is a fresh pair of feet to take on and remake the work. The collaboration between the now distinguished choreographer and her new interpreter suggests that Svengalis could learn a lot about interpersonal relations.

Natalia Osipova. Photograph © Regis Lansac

Natalia Osipova. Photograph © Regis Lansac

Natalia Osipova is one of the great classical stars of the 21st century: originally from the Bolshoi, now principal with the Royal Ballet and mentioned in the same awed tones that greet names such as Fonteyn and Guillem. She is the contemporary owner of Giselle, the role that defined Spessivtzeva’s career and it’s at the heart of Two Feet.

Over the years, Tankard’s choreography has straddled contemporary dance, ballet and theatre and none more so than Two Feet: semi-autobiographical as well as biographical and – in this 2.0 incarnation, encompassing Osipova’s story too.

Created, directed and choreographed by Tankard, the visual design – large back panels of projected photography, both natural and semi-abstract – is by her long-time partner/collaborator Regis Lansac, with a responsive lighting scheme by Ben Hughes. In front of the projections, with only a barre and occasionally a wooden chair for company, Osipova steps gracefully into the dancer’s life and guides us through it.

Osipova’s father filmed his little girl’s early lessons and they flicker in grainy black and white in between wintry trees, ancient columns and strange brickwork, archival portraits of dancers – including Spessivtzeva – and lush colour images of Ballet Russes costumery.

Natalia Osipova. Photograph © Regis Lansac

Natalia Osipova. Photograph © Regis Lansac

The work is segmented and fragmented, musically and dramatically, from the opening described above (with Osipova wearing a reproduction of Spessivtzeva’s 1934 Australian tour costume – original costume design by Dianne Bridson), through the childhood reality of so many wannabes.

The young brat Osipova – she’s a fine actress as well as a breathtaking dancer – pouts her way through AH Frank’s Every Child’s Book of Dance and Ballet from 1957 and the “Shrimping Dance”. Other chucklesome horrors, such as how to learn the Tango while wearing your mother’s gigantic shoes, amuse until laughter turns to disconcerted silence with a jolly Jingle Bells in Russian accompaniment to starvation and bulimia.

Tankard and Osipova also survey the way dance and expectations have changed over time. The sublime classical lines so excruciatingly and beautifully sought after by generations of ballerinas, finally – in the second half – give way to the modern. In place of ethereal white tulle, there is a slinky blue gown and the breaking of those heavenly physical lines. With music from Handel’s Xerxes we discover that Osipova has elbows and can make angles with her limbs.

Natalia Osipova. Photograph © Regis Lansac

Natalia Osipova. Photograph © Regis Lansac

The end – Two Feet is a two hour solo show with an interval – is stark, tragic, dangerous and beautiful. After the triumph, red roses are thrown, but sanity is melting away like winter snow. Spessivtzeva-Osipova is hopelessly lost as she splashes to her ruin through water lit to blackness.

Two Feet was always a remarkable achievement by Meryl Tankard, as dancer-creator, and she’s refashioned it beyond imagining through this partnership with the marvellous Natalia Osipova. It was the first event of the Festival to put up “sold out” signs, but you should still try – there’s always someone who foolishly doesn’t turn up.

Two Feet has one more performance at the Dunstan Playhouse, Adelaide Festival Centre on March 5. An exhibition of the original Two Feet costumes (minus one!) is in the Adelaide Festival Theatre Foyer until March 31

Comments

Log in to join the conversation.