Singer-songwriter Katie Noonan’s collaboration with the Australian String Quartet, The Glad Tomorrow, takes its name from the final line of Oodgeroo Noonuccal’s poem A Song of Hope, which ends: “To our fathers’ fathers / The pain, the sorrow; / To our children’s children / the glad tomorrow.”

Katie Noonan and the Australian String Quartet in The Glad Tomorrow. Photo © Prudence Upton

Katie Noonan and the Australian String Quartet in The Glad Tomorrow. Photo © Prudence Upton

It is this juxtaposition of pain and hope that threads through the poems by Oodgeroo Noonuccal chosen for this new song cycle, which premiered at the Sydney Opera House last night and has recently been released as an album. The Glad Tomorrow follows a similar roadmap to Noonan’s With Love and Fury with the Brodsky Quartet, which saw 10 Australian composers set poems by Judith Wright, many of whom have returned for this project.

The work of Oodgeroo Noonuccal, who was known until 1988 as Kath Walker, has proven popular with Australian composers, with Clare Maclean, Paul Stanhope, Andrew Ford and others setting her words. Malcolm Williamson’s choral symphony The Dawn is at Hand, composed in 1988, draws on several of her poems, ending – as Noonan did in this performance – with A Song of Hope.

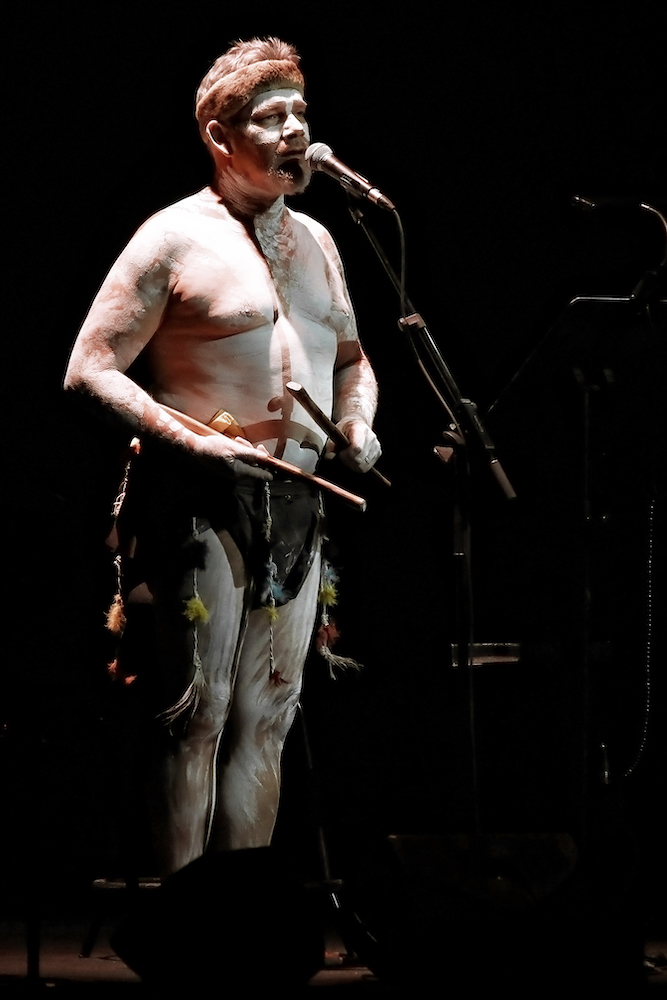

Matthew Doyle. Photo © Prudence Upton

Matthew Doyle. Photo © Prudence Upton

Following the Welcome to Country by musician Matthew Doyle, a descendent of the Muruwari people, who sung a recreation of the song Woollarawarre Bennelong and Yemmerrawanne performed in London in 1793, the Australian String Quartet and Katie Noonan took to the stage with Oodgeroo Noonuccal’s great granddaughter, actor Kaleenah Edwards. Alongside each song, Edwards recited each poem in the Jandai language, in translations by Joshua Walker, Oodgeroo Noonuccal’s grandson. She began with The Curlew Cried, which the musicians followed with an ethereal setting of the poem by Thomas Green.

While the composers chosen for this project have quite different styles, a number –Richard Tognetti, Carl Vine, Iain Grandage, Elena Kats-Chernin and David Hirschfelder – have worked with Noonan before, in many cases quite closely, and with the composers harnessing her trademark shimmering soprano and fluid leaps into her high register, there was a remarkable unity across the 10 songs.

Which is not to say each didn’t have a distinct flavour – Green’s song gave way to the biting dissonance of Carl Vine’s setting of Then and Now, perhaps the setting that drew most consciously on lieder traditions in its word-painting, particularly in the desolation of the words “no more woomera”.

Kaleenah Edwards. Photo © Prudence Upton

Kaleenah Edwards. Photo © Prudence Upton

Richard Tognetti’s angular, sometimes jagged, Son of Mine leaned furthest into a modernist aesthetic, while the slow lilt of Iain Grandage’s Song saw bending chords from the quartet evoking steel-string guitar slides. Robert Davidson’s Balance was pulsing and restless, spinning string figures mirroring the spinning coin of Oodgeroo Noonuccal’s text, while Elena Kats-Chernin’s reflective setting of Tree Grave had a touch of mournful tango to it.

Wordless vocals often feature in William Barton’s works, performed by the composer himself, but here the effect was quite different – though no less powerful – in Noonan’s hands. Barton’s setting of United We Win spanned hymn-like passages to propulsive rhythms, the final section – beginning “There is mateship now, / and the good white hand / stretched out to grip the black” spoken over glimmering strings.

The following song, Connor D’Netto’s setting of Dawn Wail for the Dead, seemed to pick up that glimmering thread, creating a sound world of softly keening dissonances, over which Noonan’s voice floated.

The amplified Australian String Quartet gave sensitive, polished performances throughout, and brought virtuosity and energy to D’Netto’s String Quartet No 2 – which opened with textures reminiscent of spectral music before building to a more urgent, Reichian minimalism – and Peter Sculthorpe’s String Quartet No 11, Jabiru Dreaming, with Sharon Grigoryan giving a moving account of the cello solo in the Estatico second movement.

While Noonan appeared to be experiencing some vocal difficulties at this performance – her high register felt a little strained at times – she was still able to deliver the goods, her sound ringing out in the final song, her own setting of A Song of Hope. Edwards’ recitations stood alone, except for in this number, which began with gentle underscoring for the poetry, the song beginning quietly before blooming.

As an encore, dedicated to Richard Gill on the anniversary of his death, Noonan sung Maranoa Lullaby, a recording of which, in a voice and piano arrangement (by British composer Arthur Steadman Loam) sung by Indigenous tenor Harold Blair in 1950, is held in the National Film and Sound Archive. Sculthorpe used the song in works such as Cello Dreaming and his Requiem (use scrutinised by Dr Christopher Sainsbury in his recent platform paper), creating the arrangement for string quartet and voice performed here, in a gentle end to the evening.

Oodgeroo Noonuccal’s poetry, however, was the beating heart of this song cycle, the rhythm of her words and their sadness, hope, wry humour and unwavering demand for change, binding the songs together. “I am personally and professionally committed to the aspirations of the Uluru Statement from the Heart,” Noonan told Limelight Editor Jo Litson recently. “So it felt like the right time to celebrate this extraordinary woman’s work.”

A moving evening of music and poetry.

Katie Noonan and the Australian String Quartet are touring The Glad Tomorrow nationally until November 10. The album is available now.

Comments

Log in to join the conversation.