Bernard B. Jacobs Theatre, New York

October 20, 2018

They say you reap what you sow, and that’s certainly the case with The Ferryman, Jez Butterworth’s riveting new play set at the height of The Troubles in Northern Ireland and now transferred to Broadway following two sell-out runs in London. By 1981, the IRA’s bombing campaign on the British mainland was at its height, men like Bobby Sands were on hunger strike in the infamous H-blocks of the Maze prison and the UK’s Conservative government was refusing to grant Republican inmates the status of political prisoners. “Crime is crime is crime. It is not political,” said a typically intransigent Margaret Thatcher, drawing rebukes from many around the world.

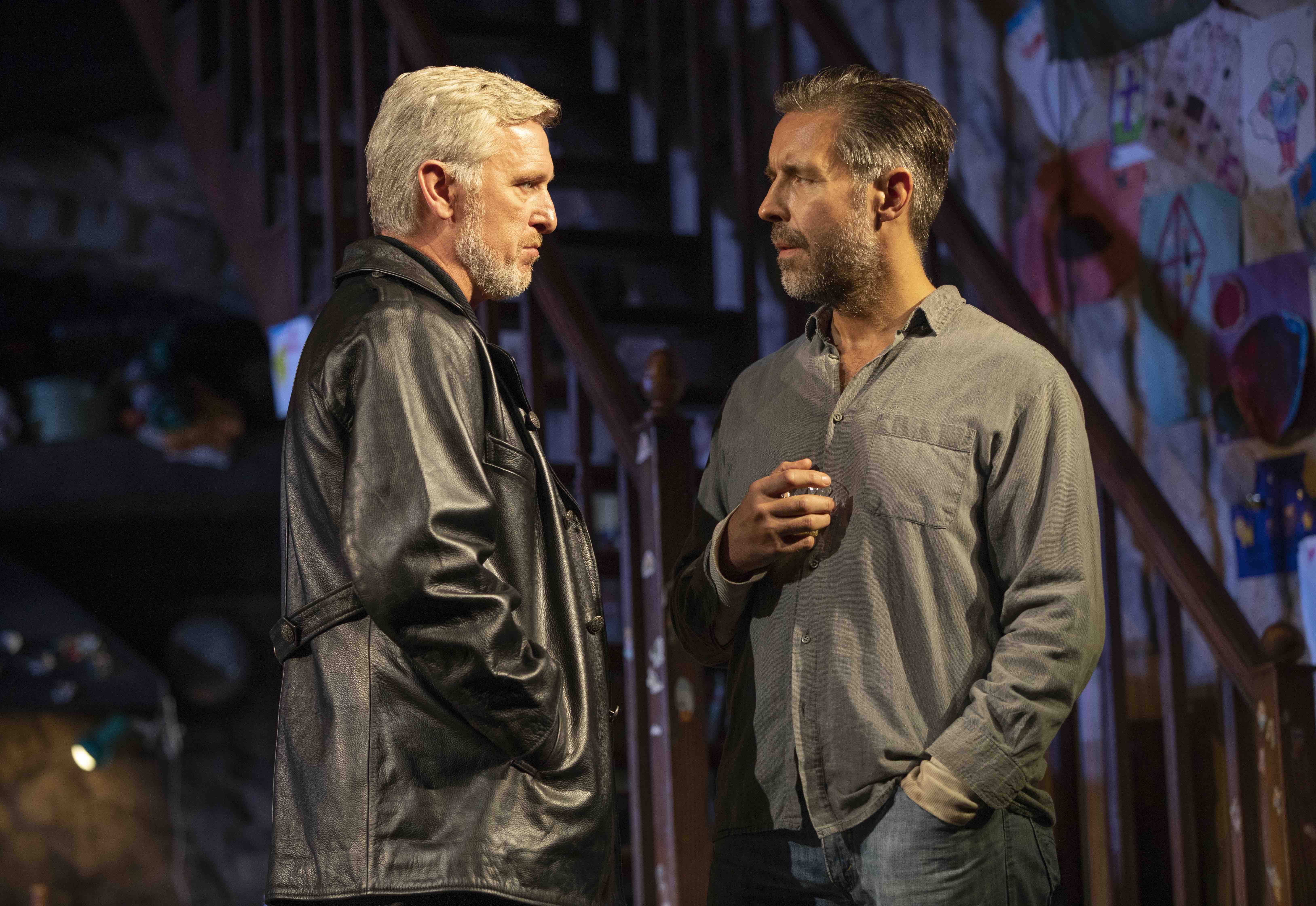

Paddy Considine as Quinn Carney and Charles Dale as Father Horrigan. Photo © Joan Marcus

Paddy Considine as Quinn Carney and Charles Dale as Father Horrigan. Photo © Joan Marcus

Outside of Belfast, however, life went on, and in Butterworth’s play, set in rural County Armagh, Quinn Carney (a broad-shouldered and sympathetic Paddy Considine) and his sprawling extended family have a harvest to bring in. It is against these twin backdrops that the pickled body of Quinn’s younger brother Seamus is discovered in a peat bog, one of The Disappeared, a group of men suspected of betraying the IRA, many of whose remains have still never been found.

Seamus vanished in 1972, we learn, at which point his wife Caitlin (a tough yet fragile Laura Donnelly, and in real life Butterworth’s partner whose family history was partly the inspiration for the play) moved in with Quinn, his wife Mary (a frail and inscrutable Genevieve O’Reilly) and their garrulous brood of seven children. Over the years, Caitlin and Quinn have grown close, so much so that Mary now spends protracted periods upstairs suffering from a series of non-specific ‘viruses’ and leaving the resourceful Caitlin to look after the family, including her own troubled son Oisin (Rob Malone).

Fionnula Flanagan as Aunt Maggie Far Away and Mark Lambert as Uncle Patrick. Photo © Joan Marcus

Fionnula Flanagan as Aunt Maggie Far Away and Mark Lambert as Uncle Patrick. Photo © Joan Marcus

Also living on the farm are three of Quinn’s elderly unmarried relatives. Uncle Patrick (the affable Mark Lambert) is a whiskey philosopher who quaffs Bushmills at 8am and recites Virgil. Aunt Patricia (a fearsome, foul-mouthed Dearbhla Molloy) had a brother die in her arms in the Easter Uprising of 1916 and has nurtured a hatred for all things English ever since (hearing Thatcher on the radio, she declares it her wish to “disembowel that smirking sanctimonious, stone-hearted sow right here on this table”). Aunt Maggie Far Away (a captivating Fionnula Flanagan) has only an intermittent awareness of the real world, but when she’s ‘present’ she regales the children with bloodthirsty folktales of the Tuatha de Danann, tells fortunes and passes on family lore.

Harvest time brings with it the Carneys’ three Corcoran cousins down from the city to help bring in the crop, young Catholic lads who idolise an IRA who are for them a daily reality. Themes of terrorism versus freedom fighters and the radicalisation of the young ensure that this essentially period piece has a contemporary edge as keen as the cut-throat razor with which Caitlin shaves Uncle Pat. But there are deeper waters here as well, not the least of which is the question of where a man’s soul resides if his body has never been found and buried (Uncle Pat’s description of Charon ferrying Aeneas across the Styx in Book 6 of The Aeneid gives the play its title).

Dearbhla Molloy as Aunt Patricia. Photo © Joan Marcus

Dearbhla Molloy as Aunt Patricia. Photo © Joan Marcus

Histories real and imagined, revenge killings, politics, religion and community clash as it transpires Seamus was killed following Quinn’s sudden departure from the IRA. Now, it seems, the local ‘Big Man’, Mr Muldoon (a chillingly matter of fact Stuart Graham) is determined to compel the family’s silence in case of questions by prying police or journalists. If past and present collide, so too do the rural and the urban. Seamus’s preserved body is found with hands and feet bound, not unlike certain prehistoric corpses that have been dug out of the peat, suggesting a cycle of violence stretching back to prehistory. Amongst all that, the stringing up of the trussed harvest goose carries an ominous echo.

Butterworth’s script is rich and varied, taking a leisurely three-and-a-quarter hours to tell its tale but never slackening in pace. For such grim subject matter, it’s a play packed full of humour thanks to the playwright’s deft portrait of this enthralling clan of three-dimensional characters. Sam Mendes’ production is flawless, giving everyone room to breathe, yet exploding with a wild and joyous energy when the Carneys decide to let down their hair – a regular occurrence for which they are justly famous it would appear. Rob Howell’s lived-in and loved farmhouse kitchen set, beautifully lit by Peter Mumford, conjures the lives of not just Quinn and Mary but of generations of Carneys who have come before them. Like much of this play, it is both timely and timeless. Nick Powell’s evocative score does much the same.

Stuart Graham as Muldoon and Paddy Considine as Quinn Carney. Photo © Joan Marcus

Stuart Graham as Muldoon and Paddy Considine as Quinn Carney. Photo © Joan Marcus

In an ensemble cast of 22 – and The Ferryman is the perfect advocate for just such a category to be introduced as part of the Tony Awards – it’s impossible to single out anyone for special mention. The Carney children – James Joseph (Niall Wright), Michael (Fra Fee), Shena (Carla Langley), and especially the young girls Mercy (Willow McCarthy), Honor (Matilda Lawler) and Nunu (Brooklyn Shuck) – are all superb as well as frequently hysterically funny. Tom Glynn-Carney, Michael Quinton McArthur and Conor MacNeill as Shane, Declan and Diarmaid Corcoran bring the strut and swagger of the city into the gentle heart of the countryside, the late-night scene where Shane boasts of his wannabe IRA connections is the play’s most unsettling. Charles Dale as the compromised father Horrigan and Justin Edwards as the gentle giant Tom Kettle shoulder their share of the burden as awkward outsiders.

Justin Edwards as Tom Kettle (holding Pierce The Bunny), Carla Langley as Shena, Willow McCarthy as Mercy, Brooklyn Shuck as Nunu, Matilda Lawler as Honor and Rob Malone as Oisin. Photo © Joan Marcus

Justin Edwards as Tom Kettle (holding Pierce The Bunny), Carla Langley as Shena, Willow McCarthy as Mercy, Brooklyn Shuck as Nunu, Matilda Lawler as Honor and Rob Malone as Oisin. Photo © Joan Marcus

Like his 2009 hit, Jerusalem, Butterworth’s new work can lay claim to being one of the great plays of the 21st century. It’s set to run until February 17 and deserves to be the hottest ticket on Broadway. This is a Ferryman well worth the paying for.

The Ferryman is at the Bernard B. Jacobs Theatre until February 17, 2019

Comments

Log in to join the conversation.