Green-Wood Cemetery, Brooklyn

October 11, 2018

The rain was beating an appropriate tattoo last night as we sat in a dank and gloomy catacomb watching Gothic horrors sprung from the pens of Mary Shelley and Edgar Allan Poe. I’m not sure which was more disturbing, the drama, the drip, drip, drip in the empty vault next to me, or the dozen or so of the dead enjoying their eternal rest in the family vault to my right. What I do know is that this was the season finale of one of the most original site-specific projects in New York and, despite the occasional fit of the terrors, a brilliantly conceived evening to remember.

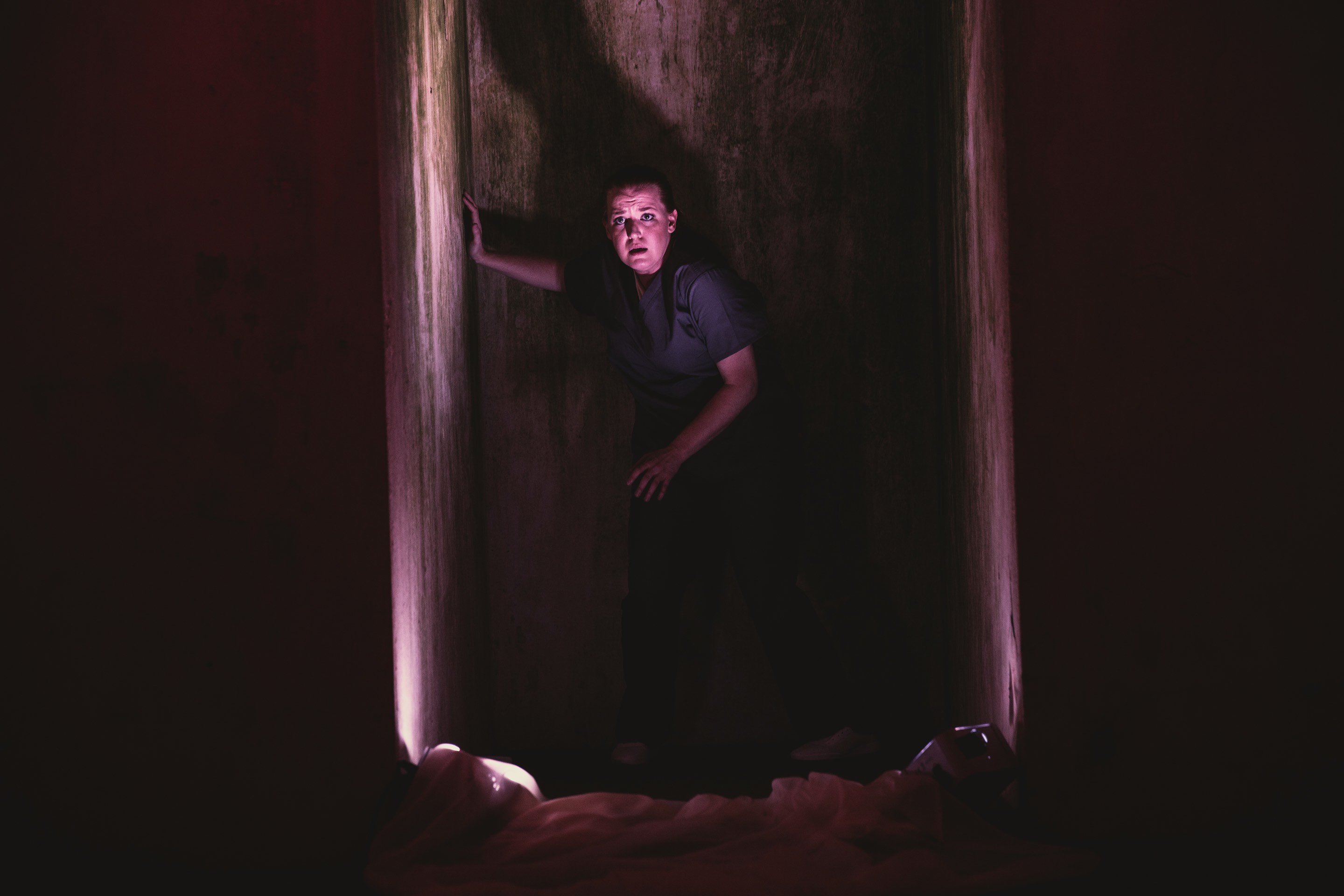

Joshua Jeremiah in Sketches of Frankenstein. Photo © Kevin Condon

Joshua Jeremiah in Sketches of Frankenstein. Photo © Kevin Condon

Opera in a cemetery may seem a macabre idea, but it’s par for the course for Andrew Ousley, the fecund brains behind The Angel’s Share, a series of ghoulishly-themed concerts featuring leading lights of the classical music world and set in the magnificent gloom of the Catacombs in the heart of Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery. Thoroughly fortified thanks to a pre-concert whiskey tasting – my favourite was the silky-smooth, yet deliciously complex Prizefight Irish Whiskey, distilled in West Cork and shipped to the US where it’s finished in American rye casks – a trolleybus takes the audience on a twilight journey to and from the Victorian vaults through a landscape dotted with the most evocative of monuments to the gone but not forgotten.

On the program were works by Cleveland-born, Connecticut-raised composer Greg Kallor: the world premiere of a collection of operatic sketches based on Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (what he hopes might be the foundation of a full-length opera) and a reprise outing for his gripping setting of Poe’s The Tell-Tale Heart. Kallor, who plays piano in both works alongside talented cellist Joshua Roman, also offered us the first performance of a solo piano tribute to Leonard Bernstein, who just happens to be a permanent resident of Green-Wood.

Joshua Jeremiah and Brian Cheney in Sketches of Frankenstein. Photo © Kevin Condon

Joshua Jeremiah and Brian Cheney in Sketches of Frankenstein. Photo © Kevin Condon

Sketches from Frankenstein begins with the audience strung out along the length of the Catacomb’s vaulted tunnel. The haunted Victor, (a bright-toned, intense Brian Cheney), runs the length of the space, torch in hand, only to hit a dead-end. Turning in terror, his menacing creation (Joshua Jeremiah, a full-toned, bass-baritone with fine diction and a terrific presence) steps ominously from one of the side chambers cutting off any chance of escape. The two men proceed to spar, Frankenstein tight-lipped and prudish, his ‘monster’, articulate and sympathetic in his desperate need for love and companionship. Sarah Meyers perfectly finessed, simple staging takes place (mostly) on a basic but effective raised platform, skillfully and chillingly lit by Tláloc López-Watermann.

Rising up from a groan of pain out of the cello, Kallor’s dynamically-charged score is intricate yet approachable with long, singable lines and plenty of moody atmosphere. If it feels a little one-note, perhaps that is because it’s currently a single extended scene with only two instruments to colour the music. What it does do extremely well is support the emotional journeys of its protagonists. The creature, of course, gets all the best lines: “How can humans be so fatuous and yet so cruel?” he sings at one point, marvelling at what mankind throws away – “their trash would be my treasure,” he laments. The sketches end with a brief love duet (the superb mezzo Jennifer Johnson Cano singing Elizabeth). As Frankenstein recounts his creation’s chilling promise that “I will be with you on your wedding night”, a hollow voice drifts in from an adjoining burial chamber to merge in haunting harmonies – a seriously chilling moment.

The Bernstein tribute, an attractive, jazz-inflected solo, gives Johnson Cano a chance to change for the second half, Kallor’s take on one of Poe’s most psychological and absorbing tales. The Catacombs were built above ground in 1851 at a time when the fear of being buried alive had a particular currency. The fate of the cataleptic Madeleine in The Fall of the House of Usher may have been partly to blame, and The Tell-Tale Heart isn’t too far removed. Published in 1843, an unnamed narrator describes how he planned and carried out the murder an old man. Having dismembered his body and concealed it under the floorboards, the murderer loses his reason as he becomes increasingly convinced that he hears the beating of the dead man’s heart.

Jennifer Johnson Cano in The Tell-Tale Heart. Photo © Kevin Condon

Jennifer Johnson Cano in The Tell-Tale Heart. Photo © Kevin Condon

Framed in a recessed alcove with a strong flavour of padded cell about it, Johnson Cano runs the gamut, her body twitching with the killer’s professed nervousness, even as she tries to convince us of her sanity. It’s a classy, voice, full-bodied and flexible, and she doesn’t miss a trick exploring the mind of a some-would-say-lunatic. Kallor’s efficient, multi-faceted score runs the gamut too, from intimate confession through mounting paranoia to ultimate terror. Again, Meyer’s direction is meticulous and powerful, the lighting throwing ghastly shadows across the singer’s features. The Catacombs happen to possess an uncanny amplification effect ensuring every note comes across loud and clear. Pinpoint diction ensures that every word carries its full weight too in a tour de force of contemporary music drama.

This is the first year for The Angel’s Share, but Ousley (who also runs the award-winning Crypt Sessions, an intimate classical music concert series in the Crypt under the Church of the Intercession in Harlem) promises they will be back next year and bigger than ever. Fans of music, whiskey and/or the Gothic should keep their eyes and ears peeled.

Comments

Log in to join the conversation.