Australian composer Robert Davidson is almost as ubiquitous in this year’s revolution-themed Canberra International Music Festival as Shostakovich. The composer’s music is often political – broadly fitting the theme of social upheaval – and has attracted attention in the past for incorporating iconic political moments.

Davidson set former Prime Minister Kevin Rudd’s “apology speech” in a commission for The Australian Voices in 2012, giving Julia Gillard’s famous “misogyny speech” a similar treatment in 2014. His 2016 work Total Political Correctness combined music with video footage of Donald Trump – then campaigning in the Republican Primaries – using excerpts from the now President’s statements on women.

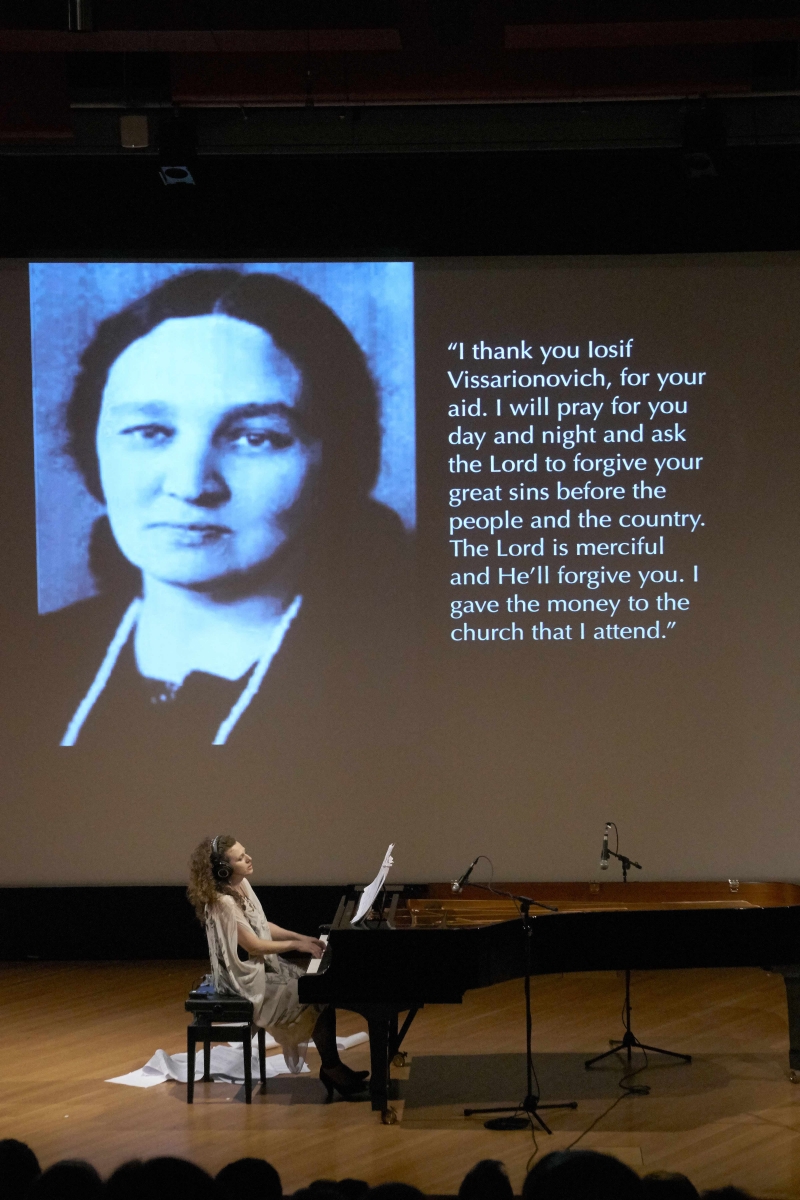

Sonya Lifschitz performing Stalin’s Piano at the Canberra International Music Festival. Photos © Peter Hislop

Sonya Lifschitz performing Stalin’s Piano at the Canberra International Music Festival. Photos © Peter Hislop

His new multimedia work for the Canberra International Music Festival, Stalin’s Piano – premiered by Ukrainian-born pianist Sonya Lifschitz – was in a similar vein, presenting a series of vignettes or portraits of 19 historical (including some living) figures, exploring the points where art and politics intersect. Harnessing the words of artists and politicians from Bertolt Brecht and John F Kennedy to Judith Wright and Joseph Goebbels, Davidson’s work focussed particularly – even obsessively – on the voices and speech of these key figures.

The opening vignette took footage and audio from Bertolt Brecht testifying before the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1947, Lifschitz providing a contemplative soundtrack as stills of Brecht, Hanns Eisler and Hitler flickered across the screen. In an approach not unlike that which Canadian composer Nicole Lizée employs in her Hitchcock and Lynch Etudes, Davidson’s images and music are intrinsically linked – the two formats duetting rather than one accompanying the other. But while Lizée’s focus is more filmic, delving into the fragmentation and deconstruction of visual and sonic material, Davidson’s work is wedded more closely to the spoken words and their historical and artistic significance.

Some voices were tightly bound to the piano part (architect Le Corbusier’s “I am a young man of 71 years old” became a rhythmic and melodic refrain over Lifschitz’s surging piano) while others drifted apart, motifs cribbed from the speeches emerging and receding from a wash of sound.

Davidson – helped in no small part by an incredibly precise performance by Lifschitz – matched the music and the cadence of the words with such exactitude that the words sounded almost sung, as if the speakers themselves were trying to follow the music. The effect brought the performative nature of speechifying into sharp relief, as musical motifs seemed to intersperse with the vocal deliveries and Lifschitz riffed on turns of phrase – Frank Lloyd Wright almost rapping in his 1957 interview with Mike Wallace and Goebbels’ thesis on politicians as artists had an unsettlingly performative feel.

Sonya Lifschitz channels Maria Yudina at the Canberra International Music Festival

Sonya Lifschitz channels Maria Yudina at the Canberra International Music Festival

A John F Kennedy/Cuban Missile Crisis vignette began with a single repeated note, played in time to a looping snatch of footage, an extra beat of video added with each new note. (JFK’s distinctive stuttering manner of speaking gave Davidson plenty of material to work with.)

At the centre of the work was Maria Yudina, Stalin’s favourite pianist – a strident and remarkably resilient critic of the Soviet regime, whose recording of Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 23 – apparently made in haste in the middle of the night, according to a dramatic story from Solomon Volkov’s dubious Testimony – was on the dictator’s record player as he died.

Lifschitz deftly narrated the story as she played, duetting with both spoken word and a fuzzy recording of the slow movement from the Mozart Concerto, creating a haunting stereo effect when she joined the solo part in unison, before moving in different musical directions.

The static of the older recordings gave the cuttings a slightly harsh edge as clips appeared and disappeared or returned with the music, but the overall effect was captivatingly scrapbooky, and the often humorous interplay of piano and film/audio was as fascinating as the exploration of art and politics.

Though there were some darker moments – atomic blasts and images from the Holocaust reminders of all that is and was at stake – figures closer to home brought laughs of recognition from the audience, with Jackson Pollock, Gough Whitlam and Robert Helpmann making appearances, before Davidson turned to his more recent material, giving Gillard and Trump the pianistic treatment.

The Canberra International Music Festival takes place in venues across Canberra, until May 7.

Comments

Log in to join the conversation.