★★★☆☆ A welcome revival of the landmark piece that has driven this company for over two decades.

Many stories are described as “timeless”, but few can rival the ancient narratives of the Aboriginal peoples of Australia for longevity. For thousands of years generation after generation have passed down these traditions, but this is a culture whose history isn’t merely spoken. Song and dance are as vital to the expression of Aboriginal life, past and present, as words. These stories, rooted in the earth, are the cornerstone of Aboriginal society, but it is also a way of life that has had to adapt to coexist alongside the urban pace of modern metropolitan Australia.

21 years ago, Bangarra Dance Theatre’s artistic director Stephen Page set out to capture the duality of contemporary Aboriginals but the result, Ochres, happened upon a mode of storytelling that was powerfully reciprocal. The fusion of Aboriginal symbolism and modern choreography not only offered a fascinating insight for non-indigenous Australians of the rich heritage of the Aboriginal and Torres Straight Island nations, but also provided a means for indigenous communities from the inner cities to reconnect with Country and discover forgotten aspects of their shared history.

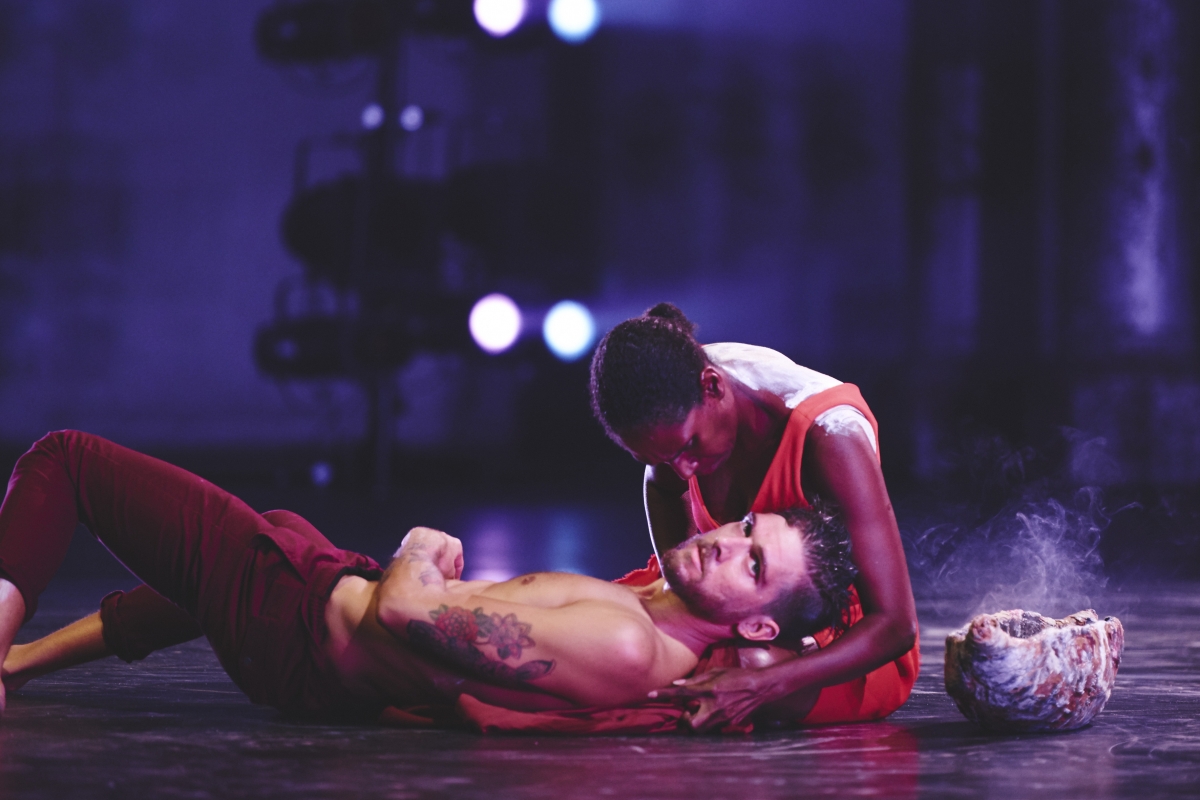

Daniel Riley and Elma Kris in Red (photo: Edward Mullvihill)

Daniel Riley and Elma Kris in Red (photo: Edward Mullvihill)

The premiere performance in 1994 was a pivotal moment, not just for Bangarra, but for all Aboriginal artists. Ochres was a blazing statement of the creative wealth and contemporary relevance of indigenous expression, both of the present day and the ancient past. This revival, appropriately staged in Redfern where this company was born, is a potent reminder of why Ochres had such a seismic impact.

Inspired by the four coloured clays – yellow, black, red and white – that have been used ceremonially by Indigenous Australians for millennia, this piece taps into the most sacred rites of Aboriginal culture. However the narratives that Page and his choreographic collaborator Bernadette Walong-Sene explore in Ochres also illuminate universally human experiences. There is a clear imperative responsibility, an expression of sincere respect for the mystical significance of the ancient traditions this piece draws on, but it is also proudly forward-facing, acknowledging the importance of accessing a more contemporary means of communication.

In Yellow, womanhood is evoked with loose, crouched undulations and organic sweeps. Seven female dancers stalk the stage, breaking from a fluid mass into shapely, serpentine duets, their figures low to the ground, faces alert but questioning. The movement is underpinned with flowing gestures punctuated by long, sensual lines, but this femininity is infused with a primal danger.

White, from Ochres (photo: Jhuny-Boy Borja)

White, from Ochres (photo: Jhuny-Boy Borja)

Black is a study in testosterone and masculinity. Djakapurra Munyarryun, painted in the traditional manner, spear in hand, provides a cultural anchor as the six bare chested dancers leap and scuttle with a ferocious charge. These warrior figures anoint themselves with ochre across their faces, moving with deliberate, muscular intention. They spar with each other, powering through a barrage of kicks and lunges, duelling with wooden swords before becoming the animals of the outback, swatting at flies and strutting like emus.

These gender archetypes come together in Red, the most narratively specific part of Ochres. A series of male and female relationships are presented using a tug-of-war as an idée fixe, although after the playful capriciousness of youth these interactions become more fraught. There are hints of domestic violence, the corrosive influence of alcohol and drugs, the fear and delirium of sickness or perhaps addiction, all aspects of modern Aboriginal life that speak to the social crises that have attacked the fabric of indigenous communities in the inner cities.

This tension finds release in the catharsis of the final section, White, a beautiful cadence of physical poetry with the entire ensemble on stage together for the first time. Djakapurra Munyarryun and Elma Kris are the embodiment of the ancient past, the voices of ancestors that resonate through the ages. The rest of the company, fully painted now in white, bring us into the spirit world, becoming human totems balancing in carefully cantilevered shapes that seem to defy gravity.

Black, from Ochres (photo: Jhuny-Boy Borja)

Black, from Ochres (photo: Jhuny-Boy Borja)

Even after two decades this choreography feels fresh, insightful and creatively impressive, although David Page’s score remains very much a product of the 90s, and this occasionally dulls some of the finesse of this work’s drama. This company have an exhilarating physicality, unhindered by the self-consciousness of a more formal technique, but there are times where a lack of discipline allows the tension of this piece to sag.

Neither flaw however threatens to rob Ochres of its rightful place among this company’s greatest achievements. Perhaps most impressive is the notion that this fusion of styles, now so familiar to Australian dance lovers, was pioneered through this work. The combination of ancient and modern could easily feel abrasive or inauthentic, but Ochres effortlessly achieves a well-judged equilibrium. Both Page and Walong-Sene have individually distinctive choreographic voices, but what they share is a thorough understanding of the balanced intermingling of old and new. In a very touching sense, this is dance that seems built from the inside out, offering something not only visually and dramatically accomplished, but also extraordinarily poignant.

Bangarra Dance Theatre present Ochres at Carriageworks until December 5.

Comments

Log in to join the conversation.