This review was originally published on February 12, 2016 as part of Opera Australia’s 2016 Sydney Season.

Joan Sutherland Theatre, Sydney Opera House

February 11, 2016

For aficionados, Verdi’s Luisa Miller represents the start of his middle period, the fertile five years that saw hits like Rigoletto and Il Trovatore culminate in La Traviata. And yet, like its immediate successor Stiffelio (another fine opera), productions of Luisa Miller don’t come along all that often. It has its hit tenor aria – the lilting Quando le sere al placido, popularised by Domingo among others – and its ought-to-be-a-hit soprano aria – Lo vidi e’l primo palpito. It has fine roles for baritone and two basses, stunning ensembles, romance, villainy… what more does an opera need? For all the above reasons, plus the chance to see Nicole Car fresh from overseas triumphs in her first Verdi role, this was one of Opera Australia’s buzzier openings. No disappointments either, Luisa Miller is an outstanding evening of music and drama.

Based on Schiller’s play Love and Intrigue – one of his social equality sturm und drang specials – Verdi and his librettist Cammerano tamed some of the revolutionary aspects of the original, pushing it safely back in time and skewing their take towards the love story. A decade later, and the composer might have balanced the sentiment with a bit more political jiggery-pokery, but not in 1849. The plot begins with two young people in love – Luisa, daughter of a retired soldier and Rodolfo, the local Count’s son in disguise. When Rodolfo’s love is revealed, his father forbids him to see his low-born sweetheart while she is duped into declaring her love for Wurm, the Count’s weasely steward. Result: tears, trauma, a poisoned chalice and a drawn-out double death scene.

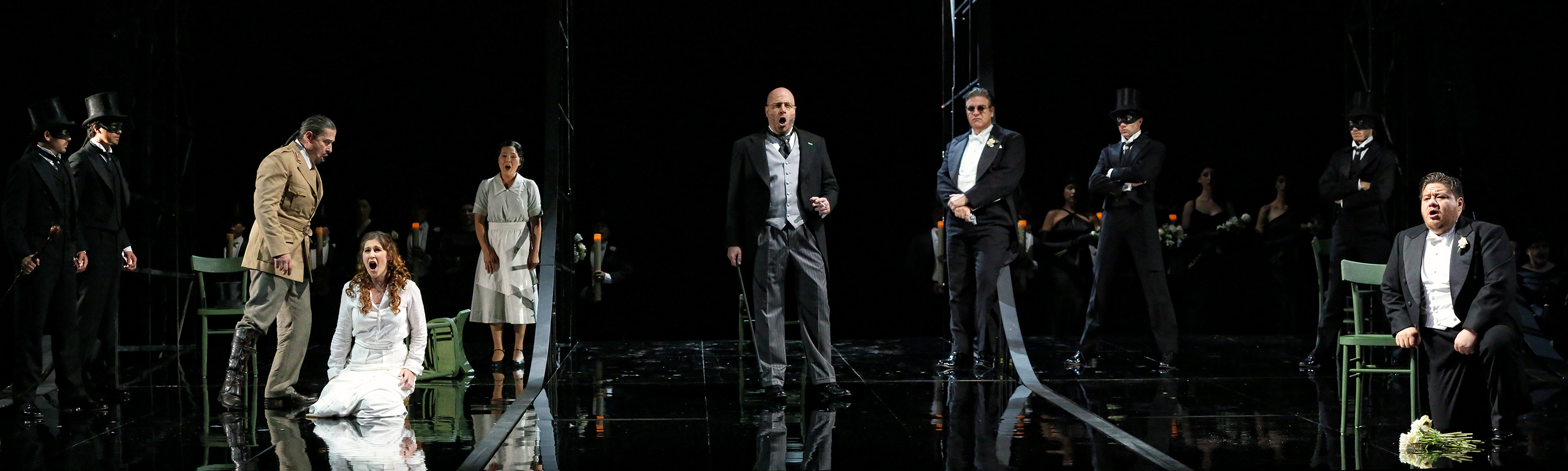

Principal cast of Opera Australia’s production of Luisa Miller; Dalibor Jenis, Nicole Car, Eva Kong, Raymond Aceto, Daniel Sumegi and Diego Torre © Prudence Upton

The underlying themes – a critique of aristocratic snobbery while lauding an inherent bourgeois decency – don’t resonate today the way they did for a Beethoven or a Verdi. Still, it’s hard not to find yourself rooting for the upright, principled Miller or his sweetly innocent, yet doomed daughter given the strength of the music that Verdi has lavished on his more honourable characters. And what the composer lacks in forward-looking dramaturgy, he makes up for through imaginatively constructed aria and scene structure and novel orchestrations (there’s an organ, bells and a cimbasso – that’s a now obsolete five-valved trombone-like thing that I’ll admit I’m not sure I heard). He even ditches the traditional banda in favour of some atmospheric off-stage Tyrolean horns. In short, it’s a beautiful score that’s both imaginative and tuneful.

Opera Australia’s new co-production with Opéra de Lausanne here receives its Sydney premiere. Giancarlo Del Monaco’s solid staging features a grimly stylised Greek chorus (you’re never quite sure if they are at a wedding or a funeral) who endlessly circle the stage. In the centre, the principals are treated in a more naturalised manner. The whole production plays out against Jacopo Pantani’s austere black and white marble design – a sort of monument to the perfect bourgeois family, literally turned upside down. William Orlandi’s sumptuous Edwardian-flavoured costumes (also in black, white and greys) plus Vinicio Cheli’s crisp lighting design both make distinguished contributions.

Del Monaco can’t escape the melodramatic shortcomings of the work – all those reveals, the poison, the 15-minute death scene, and the diabolical doings of the duplicitous Wurm (with that name, could he be anything other than a dyed-in-the-wool villain?). Indeed, at times he embraces it. But when the musical standards are this high, the odd snigger at an over-the-top opera moment hardly seems to matter. This is one of those evenings where the three stellar principals, the sterling supporting cast, the rich singing of the OA chorus, and Andrea Licata’s sure hand on the tiller of an excellent orchestra all conjoin to elevate proceedings towards an operatic Nirvana.

Nicole Car performs the title role in Opera Australia’s Luisa Miller © Prudence Upton

Nicole Car is remarkable in her first Verdi role, singing with impressive amplitude, yet never sacrificing detail and attention to text for sheer decibels. That said, when lung power is called for she soars over the ensembles, easily matching her fellow singers, no matter how stentorian. Meanwhile, she’s able to pull back to pick out an elegant staccato coloratura line, shape the descent from a passionate top note, or ‘die’ gracefully without a crack or a gurgle. The duets with her noble-minded, adoring father and her passionate, unstable lover are among the evening’s many highlights. With her warm stage persona, the role of Miller’s gentle yet determined daughter was made for her, and she owns it from the moment she rises from a mournfully symbolic bower of roses up until the final curtain call. The opening night crowd deservedly went wild for what was a genuine succès d’estime.

Slovakian baritone Dalibor Jenis (Car’s 2014 Onegin in Sydney) is in glorious vocal form as her noble paterfamilias. Allowing just a hint of age to occasionally colour the voice, his powerful tone and creamy legato singing make him a dream Verdi baritone. His heroic upper register rings out straight as a die, never over-covering at the top. His radiant aria, Sacra la scelta è d’un consorte (The choice of a husband is sacred) is in many ways the opera’s ethical theme song and Jenis makes every note count. A sympathetic figure, his dramatic relationship with Car rings entirely true. Equally exciting is Diego Torre as the wild-eyed Rodolfo, managing to create a believable character out of a bit of a histrionic. He uses his substantial voice with considerable sensitivity, scaling it back (more often than he managed in Don Carlos) to powerful effect. He deals in a nice line in inflected recitative, and of course those top notes are golden. A beautifully shaded Quando le sere al placido drew a string of bravos, only marred by a little tiredness in the ensuing cabaletta on opening night. However, his final duet with Car (a cracking number as good as anything Verdi ever wrote) was gripping. And between the two of them and Jenis, the score’s several engaging trios are memorable as well.

Daniel Sumegi (Wurm) and the Opera Australia Chorus in Luisa Miller © Prudence Upton

Luisa Miller sports a matched pair of wicked basses – a bit of a Verdi speciality – and the excellent American singer Raymond Aceto duly went head-to-head with his Australian counterpart and henchman Daniel Sumegi. Aceto as the intriguingly complex Count Walter has a warm, subtle voice, easily able to climb to the necessary heights and deliver a thrilling top note to end his Act I aria, Il mio sangue la vita darei. He’s a nice actor too. Wurm on the other hand is one of Verdi’s least subtle villains. He’s unremittingly evil and so Sumegi’s rather unremitting, cavernous bass proves a perfect match. Listening to these two operatic behemoths in the surprisingly upbeat duet where each realises that they may both be doomed is a genuine treat. Mezzo-soprano Sian Pendry is more than adequate as the ‘other’ woman, singing with warm tone and making plenty of a rather underdeveloped role.

Down in the pit things are equally ideal. Licata is an instinctive Verdian, pacing and shaping the score with great skill. There are lovely contributions from horns – on and offstage – as well as woodwind, and especially the prominent clarinet part (Phillip Green). Most impressive though is the string tone, which is a dream throughout. The OA chorus overcomes some tricky sight lines to deliver a detailed account of Verdi’s many varied ensembles.

As I said at the start, Luisa Miller doesn’t come around that often. It’s surely one of the riskier numbers in this year’s OA programme and Lyndon Terracini deserves a damn good pat on the back for taking a chance on a rarity that pays off so spectacularly. No fan of 19th-century Italian opera – or good singing in general – can afford to miss such a golden opportunity.

Luisa Miller is at the Arts Centre Melbourne until May 27

Comments

Log in to join the conversation.