When the then-president of Lincoln Center William Schuman advised four of his colleagues to set up the first Mostly Mozart Festival back in 1966 it was intended to provide a diverse mix of American freelance classical musicians with a source of income across the hot, artistically quiet New York summer. Since then, the repertoire has widened considerably beyond its original brief to include other ‘Classical era’ composers, and then ‘Neo-classical’ composers – indeed, much of today’s program has only the most tenuous of connections to WA Mozart. Meanwhile, its resident band, the Mostly Mozart Festival Orchestra (MMFO), has developed apace under its two music directors (Gerard Schwarz, appointed in 1984, and Louis Langrée, MD since 2003).

Mark Morris Dance Group in Empire Garden. Photo © Stephanie Berger

Mark Morris Dance Group in Empire Garden. Photo © Stephanie Berger

Whether any of that matters is a moot point. With precious little classical music in the Big Apple in July and August, and many New Yorkers decamping to places like Tanglewood or Marlboro, what counts is variety and excellence, and this year’s Festival offered plenty of both. The opening big ticket items were mostly known quantities: Barrie Kosky and UK company 1927’s visually striking Magic Flute had acclaimed runs at this year’s Perth and Adelaide Festivals; the Mark Morris Dance Group’s popular program included previous hits Empire Garden and V alongside Sport, a new work set to Satie’s witty Sports et Divertissements featuring Morris’s takes on swimming and blind man’s buff. (Sadly the performance I was due to attend fell victim to New York’s much-reported power outage.)

A magnet for tourists and those who choose to stay in town, Mostly Mozart earns its bread and butter through name recognition and big hitters, hence a degree of the conventional in its mainstage concerts. But even a populist-sounding concert like the Festival closer Mozart à la Haydn can conceal a challenge – in this case Schnittke’s Moz-Art à la Haydn, which shared the bill with Steven Osborne in Shostakovich’s Piano Concerto No 2.

Joshua Bell plays Dvořák was admittedly more conventional (Mozart’s Prague Symphony, Kodály’s Dances of Galánta and the Dvořák Violin Concerto), but the chance to hear the charismatic Bell was nevertheless irresistible. One of Mozart’s most joyful works, Langrée led the Prague Symphony in a spirited, lightly sprung yet slightly yearning performance with ceremonial percussion nicely weighted against scurrying string textures. You really don’t hear enough Kodály these days, and although I’ve heard the Galánta Dances played with greater swagger, it was still a pleasure to catch them live in a pacey, colourful performance with especially distinguished woodwind solos.

Joshua Bell © Benjamin Ealovega

Joshua Bell © Benjamin Ealovega

Dvořák’s tangy Violin Concerto is another work too infrequently heard. Lacking the sheer technical demands (and length) of the Brahms, it was particularly good to hear as prestigious a soloist as Bell take it for a spin. Investing the opening movement with some welcome Paganinian fire, he proved a fine advocate (even with the safety net of the score and some seat of the pants moments). The Slavonic Rondo Finale suited Bell’s silvery tone especially while an arrangement of a Chopin Nocturne for violin and orchestra made the perfect encore. By the way, the extra seating on the sides and back of the David Geffen Hall concert stage not only provided some extra revenue, it gave the whole concert an appealingly intimate feel.

For geeing up a warhorse it would be hard to beat Pekka Kuusisto’s wily take on Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons. The Finnish virtuoso – who Australian audiences will know for heading up the Australian Chamber Orchestra’s ACO Collective – has an enviable reputation for defying expectations with quirky yet thoughtful programming and spirited music-making and this concert was no exception. In tandem with the MMFO, British violinist turned conductor Andrew Manze, and bassist Knut Erik Sundquist, he set out to explore – as Manze put it – the “music beneath the music” by inserting folk duets into the cracks between the movements.

Opening with Bartók’s Romanian Folk Dances as curtain raiser, Kuusisto slipped seamlessly from 20th-century folk-inspired masterpiece for strings into the real thing in the form of intimate duets with Sundquist. The Vivaldi offered more of the same, this time all the more remarkable since the connection between Vivaldi and folk music from Finland and Norway would seem less obvious to say the least. With soloists and conductor clearly enjoying the occasion to no end, this was infectious concertising with some wonderfully off-piste contributions from Kuusisto as soloist (I’ve never heard galloping horses actually whinny in Autumn.) At one point we were even treated to some mischievous Nordic whistling.

Mostly Mozart Festival Orchestra with Pekka Kuusisto and Knut Sundquist. Photo © Lincoln Center

Mostly Mozart Festival Orchestra with Pekka Kuusisto and Knut Sundquist. Photo © Lincoln Center

Over the road at 10pm, in the cabaret-style intimacy of the Kaplan Penthouse – one of my favourite New York concert venues – the festival’s A Little Night Music series gave us another hour of Kuusisto and Sundquist. Replete with a line in Scandinavian patter (dry, sly and ever so wry), the two musicians bounced off each other like a pair of seasoned stand-ups while delivering an infectious program comprising a set of minuets, a set of “extremely sad” music, a set of “extremely joyous” music and a finale that, we were told, “will make you want to go home”. With Bach and Tallis rubbing shoulders with good old “Trad” and a slice of Polish tango it was an enjoyably eclectic musical bean feast, not the least of which was Kuusisto informing us that the traditional Finnish polska was a dance in a straight ¾, whereas its Swedish equivalent was in triple-time, coming over as something like “a drunken moose”. Pure joy!

New music in intimate settings has become one of the Festival’s draw-cards in recent years, and other highlights would have to include NY-based string quartet Brooklyn Rider’s Mostly Mozart debut as part of the A Little Night Music series. Leading with an involving account of Philip Glass’s just over a year-old Eighth String Quartet, this was a chance to hear approachable contemporary music played by a group with a unique aesthetic.

Equally involving, if tougher nuts to crack, were the modernist works played by ICE (International Contemporary Ensemble), a collective of New York’s finest exponents of new music and something of a Mostly Mozart staple these days. With fascinating music by six living composers from five different countries, plus three less commonly encountered instruments – the Hungarian cimbalom, the Persian kamancheh and the Japanese shamisen – the 20 musicians, two singers and a battery of electronics made for a highly original musical evening. Kurtág’s Tre Pezzi, Op. 38 and Tre Altri Pezzi, Op. 38a for cimbalom and clarinet and Kate Soper’s The Ultimate Poem is Abstract were firm favourites here, but best of all was the world premiere of Dai Fujikura’s spiky, yet tuneful, Shamisen Concerto, a brilliant new work that effortlessly combines an Eastern instrument with a traditional Western musical form.

Under Siege. Photo © Ding Yi Jie

Under Siege. Photo © Ding Yi Jie

Not everything was a palpable hit. With its stunning design of a stage overhung with ominously clacking suspended scissors, Chinese dance maker Yang Liping’s Under Siege talked a good fight, yet despite a plethora of impressive visual effects, the bare-bones storytelling often felt slow and long-winded.

The multi-faceted production tells the story of the events leading up to the Battle of Gaixia (202BC), much of it familiar from the highly successful film Farewell, My Concubine. Despite being the founder of what would become modern China, the leader of Han (Liu Bang) is portrayed here as the double-dyed villain, with the more charismatic Chu leader (Xiang Yu) the tragic hero of the tale. The statesman Xiao He narrates how the duplicitous general Han Xin brings down the Chu forces, and how Yu Ji, the beloved concubine of Xiang Yu, kills herself rather than allows herself to become a pawn in the military game.

Performances were flawlessly disciplined, the dancers combining athleticism with subtle grace, especially the dynamic Ge Junyi as the doomed Xiang Yu and Xiao Fuchun as the mercurial renegade Han Xin. The two pipa players (Feng Xiaofan and Wang Hanrui) were also excellent, and thanks to subtitling, all came over as clear as day. But running at an unbroken hour and forty minutes, one couldn’t help feeling that cutting at least half an hour would make for a more compelling narrative.

The Black Clown. Photo © Richard Termine

The Black Clown. Photo © Richard Termine

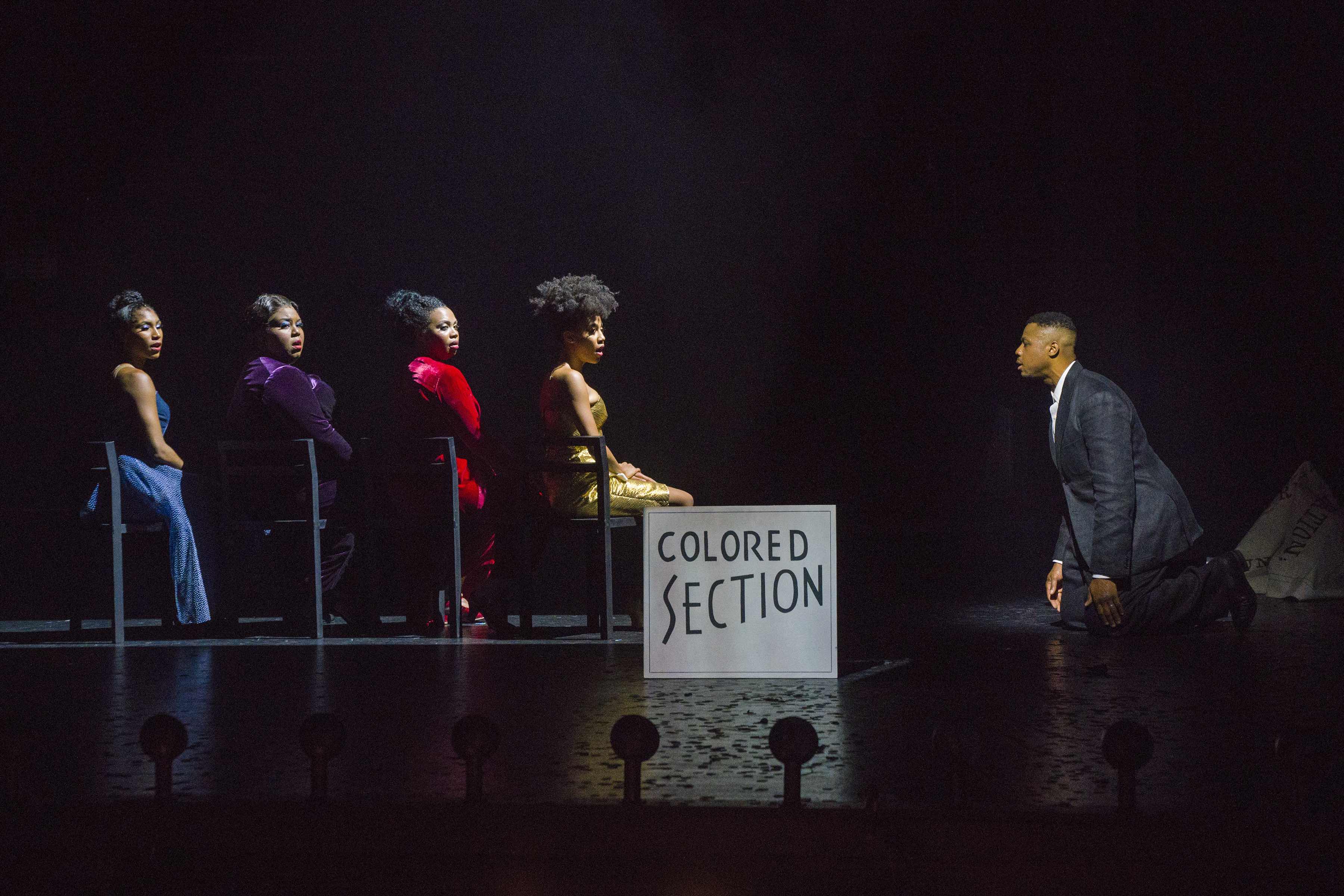

For me, however, the standout work had zero connection to Mozart. Langston Hughes’ The Black Clown is, in the poet’s own words, “A dramatic monologue to be spoken by a pure-blooded Negro in the white suit and hat of a clown, to the music of a piano, or an orchestra.” Thanks to the prodigious talents of co-adapters bass-baritone Davóne Tines and composer Michael Schachter, plus the outstanding work of director Zack Winokur, this 70-minute American Repertory Theater production erupted onto the modest stage of the Gerald W. Lynch Theater with all the passion and dramatic wattage of the finest Broadway show.

Tines and Schachter have expanded Hughes’ 78-line, 1931 poem into a veritable Homeric epic, setting it for a band of 11 and an ensemble of 12 (plus Tines himself as the titular character). Crackling with energy, both musical and dramatic, Schachter casts a dazzling orchestration that includes trumpets, wind, banjo and a plethora of percussion over music that taps into every genre of the black American musical experience: work songs, the blues, the Charleston, jazz, spirituals, gospel and all the way up to R&B. In this adaptation, and with this degree of focussed, concentrated, and frequently raw emotion, four lines of Hughes was able to easily sustain itself over a five-minute sequence.

The poet casts his ‘Everyman’ protagonist as a black clown, hiding behind a half-involuntary comedic mask while struggling to rise in a white-dominated society that pretends at opportunities that simply don’t exist. “Three hundred years / In the cotton and the cane, / Plowing and reaping / With no gain— / Empty handed as I began” says the text, while the staging, which breaks out in a fleeting moment of joy as an Abe Lincoln on stilts emancipates the slaves, soon falls back into the bleak imagery of segregation and Jim Crow America.

The Black Clown. Photo © Richard Termine

The Black Clown. Photo © Richard Termine

Winokur, with prop-eschewing ingenuity, creates a sequence of extraordinary images that sear themselves into the brain. Best of all are the cast. Led by Tines’ rich, flexible bass-baritone, they sing the pants off of this music and dance up a storm to Chanel DaSilva’s inventive choreography. The sheer concentration of talent on the stage a testament to Hughes’ final exhortation: “Rise from the bottom, / Out of the slime! / Look at the stars yonder / Calling through time.”

Broadway producers and festival directors take note: this unique, powerful, electrifying and important show deserves a further life. Meanwhile, kudos to Mostly Mozart for taking a punt on The Black Clown.

Comments

Log in to join the conversation.