Beethoven, burglary and the Baroque form the cornerstones of next year’s imaginative programme.

In the introduction to the Australian Chamber Orchestra’s new season brochure, Richard Tognetti writes that his most triumphant musical experience was not as a player (of 1,160 works to date and counting) but as a listener. He goes on to recall a student experience his first time in Europe at a time when he was “alone, free, headstrong, full of Romantic ideals”. Landing from Australia at Frankfurt airport he was headed for Davos in Switzerland. “It was 7°C and foggy,” he reminisces . “I took a train through the miserable Rhein-Main-Gebiet up into Zürich where I changed trains to a mountain village high up in the Graubünden region of Switzerland. As the geography rose, so did my spirits. For the duration of the trip I was listening over and over to Beethoven’s Op. 131 Quartet in an arrangement for strings by Dmitri Mitropoulos, on an old Walkman.” At the same time he was reading Thomas Mann’s Der Zauberberg without realizing that the place he was headed was the very ‘Magic Mountain’ where the sanatorium in the book is set. “When I arrived I was full of Beethoven’s crazed delights and Thomas Mann’s insights. It was snowing and I was impressionable, but really what a triumph,” he says.

The inspirational Davos in Switzerland

The inspirational Davos in Switzerland

That early inspirational moment lies at the root of the ACO’s 2016 season, a programme centered on the late Beethoven String Quartets, works that many consider the pinnacle of the chamber repertoire. “As a student at the Con they were always sitting there the way Everest always sits there for any hiker,” he tells me, “I didn’t think I’d ever find the portal through which I could fly and enter into Beethoven’s world”. But then the “double whammy” of Mann and Mitropoulos opened a door. “From then on Opus 131 was one of my favourite pieces, and it wasn’t in a quartet version that I first fell in love with it. It was an arrangement for strings.”

That sense of scale should suit the ACO as the crack ensemble enters its 41st year (and Tognetti’s 26th). The works are dotted throughout the season and should be ear-openers for anyone wanting to hear them with the added heft of full string band. “It broadens the tonal palette and the music works better in a larger space,” explains Tognetti. “As far as, ‘oh, it loses the intimacy’ goes, well, I’m sorry but you’ve lost the intimacy as soon as you go into a big concert hall. The notion that we’re just meant to be presenting what you can listen to in the comfort of your own home is a bit of a – if I can use the Australian term – a bit of a furfy. This is a different experience so you lose certain things but gain others.”

Richard Tognetti

Richard Tognetti

That sense of difference and a preparedness to embrace a wider range of musical experience is what has set the ACO apart over many years now. Tognetti is an artist who prefers his music not to be set in aspic and resolutely refuses to be pigeonholed whether he is playing music from the 18th or the 21st centuries. “I think that that’s essential in art,” he says. “If you have the copyright lawyers or the historically informed performance police trying to stop the process it shackles you. And the great performers of the early music movement were never about that anyway.”

That segues rather neatly into the item that has really piqued my interest on the programme, a concert intriguingly called Theft (or what I’m calling my second ‘B’ – for burglary) that will involve musicians, experts, lawyers and thieves. I’m keen to know more. “Well, just to be cheeky, everyone who sits there listening to music out of copyright is in possession of stolen goods,” Tognetti laughs. “And it’s always the lawyers who drive this when they smell money.” So, Theft aims to examine music’s past and present in order to ask questions about the nature of creativity and ownership. Is a certain piece inspiration or plagiarism? Homage or robbery?

Who owns E.T. – Williams or Dvořák?

Who owns E.T. – Williams or Dvořák?

I ask for an example and Tognetti hums a sequence from the film E.T. “It’s not just borrowed or inspired by Dvořák and his Dumky Trio but it’s taken, stolen, lock, stock, and barrel,” he explains. “Now if I were to take an original theme from John Williams I’d be accused of plagiarism, and copyright lawyers would quite happily see me in metaphorical handcuffs. But I wonder who has the copyright over that theme? I rather suspect that John Williams and his lawyers do. So that’s the conundrum that we are looking at.” He feels equally strongly about the notorious Kookaburra sits on the old gum tree tune, used as a counter melody in Men at Work’s 1980 hit Down Under. “For me, it’s a folk tune that has become a part of the vernacular,” he maintains. “If you’re not allowed to use and re-use those themes it takes oxygen out of the creative process. We should be able to use the Beatle’s Yesterday like we should be able to use Happy Birthday.”

“Bach, of course, ‘stole’ from Vivaldi. It’s just part of the process. Stravinsky borrowed (or stole) folk tunes from the area where he grew up and it’s the same with Janáček, Bartók, Vaughan Williams and Percy Grainger. But then we hit the 20th century and we get this copyright issue where if you write more than four to eight notes in a row and they sound similar you’re in a court of law. The most blatant example is the Verve song Bittersweet Symphony, which was taken from the Rolling Stones. The Stones got all the copyright even though The Verve turned it into this successful song – and it sounds nothing like the Rolling Stones!”

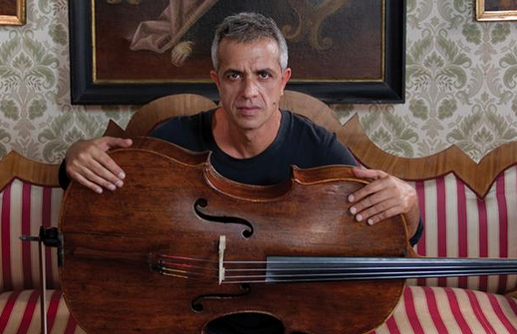

Italian cellist Giovanni Sollima

Italian cellist Giovanni Sollima

The third ‘B’ might well be Bach, but it could equally well stand simply for Baroque. As usual in an ACO season the players are ready to strap on their gut strings and turn back the clock to the 18th century. Tognetti will lead them through a concert featuring two of Bach’s Orchestral Suites alongside some Vivaldi and a new work by Elena Kats-Chernin. They will also have a little help from friends old and new. The old first, and maverick Italian cellist Giovanni Sollima, who wowed Australia (and me included) with his eclectic performances last year, returns to give a series of concerts with Satu Vänskä and Maxime Bibeau. The combination of the Baroque (Monteverdi and Leo) with the Romantic (Rossini and Paganini) and the 20th century Berio and Scelsi is typically provocative. Leading Aussie guitarist Slava Grigoryan will play Rodrigo’s ‘Aranjuez’ in a concert that includes Ravel and Beethoven’s high-octane Seventh Symphony.

The new will see the ACO get to make friends with Russian coloratura Julia Lezhnaeva (a hit at 2014’s Hobart Baroque), who returns down under to make what will be her touring debut in many of our cities. The 25-year-old will sing Porpora, Handel and Vivaldi it what must surely be one of the hotter tickets of 2016. The other stellar guest will be the distinguished Russian pianist Elisabeth Leonskaja who will play Mozart’s Jeunehomme Piano Concerto – probably his first pianistic masterpiece. Described by the UK’s Telegraph newspaper as having “something precious and rare,” Leonskaja is a player firmly in the tradition of the 20th-century greats – her mentor was the mighty Sviatoslav Richter – and this tour will be her long-overdue Australian debut.

Russian pianist Elisabeth Leonskaja

Russian pianist Elisabeth Leonskaja

On the subject of the new, thanks to a meeting on last year’s Timeline concerts, the ACO will collaborate with Synergy Percussion on music and the movies in an event called Cinemusica. “Tim Constable and I started dreaming and came up with the idea,” explains Tognetti. “Of course the most obvious piece to do is Bartók’s Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta, but for many, many, many years I’ve been an admirer of Thomas Newman’s music. He’s the sort of film composer changing the course of sound used in cinema, especially with American Beauty but also the way he uses strings in In the Bedroom. It isn’t often performed in the concert hall and so we thought it would be interesting to try and bring this music alive as it’s so percussion based.”

The other new kid on the block comes in the form of the freshly renamed ACO Collective, which will be lead this year by violin wiz Pekka Kuusisto. An artist firmly in the Richard Tognetti mould, acquiring his services has been quite a coup for the company. “To quote Glenn Gould talking about CPE Bach, ‘the quirky quotient is very high’”, says the ACO’s leader of his Finnish colleague. “Pekka takes an oblique look at mainstream repertoire – so it’s new ways of looking at old things – but he’s also heavily involved in new music as well as being a formidable fiddler.” The new is very much to the fore with Nico Muhly, Erkki-Sven Tüür and Bryce Dessner on the programme, all contemporary composers who, without trivializing it, have a kind of common touch. “And thank God for them!” exclaims Tognetti “Old white men in cloistered environments haven’t necessarily done the music business a great service in the recent past. Thank God there are people in the popular music world who are looking over the fence and are being inspired by the sounds of Darmstadt and post-Darmstadt and being able to transmit those sounds in a way that is – and I’m going to use the word – accessible.”

Pekka Kuusisto

Pekka Kuusisto

Accessible, yes, but this is frequently complex music that somehow manages to be genuinely engaging. “Yeah,” Tognetti agrees, “and the lineage of some of this new music is interesting. Jonny Greenwood comes from Penderecki, and many of these musicians have been inspired by Ligeti, but they’ve been able to liberate their music from the environment in which it was composed. I was there in the ‘80s in Europe and there was a real fear of popular music. Arvo Pärt was described disparagingly to me by Heinz Holliger as ‘Neo-Neanderthal’. I was just a student at the time but I thought ‘this is offensive and wrong’ – and who is Heinz Holliger as a composer!”

It’s that kind of fighting talk that has defined Tognetti’s ACO in the past and looks likely to forge the company’s path into the future. After 25 years at the helm, does it get any easier? “It’s always a nervous time,” Tognetti admits as I offer my congratulations. “It’s a bit like a wine vintage – you’re never quite sure how it’s going to come out.”

Comments

Log in to join the conversation.