Orchestral Recording of the Year 2017

Chamber Recording of the Year 2017

Instrumental Recording of the Year 2017

Vocal Recording of the Year 2017

Opera Recording of the Year 2017

In 2015, the Limelight Recording of the Year by almost unanimous consent went to a blockbuster recital of Chopin and Mozart by master pianist Grigory Sokolov on a major label: Deutsche Grammophon. Last year, it was rare repertoire by an established ensemble that won out: Herbert Howells by Stephen Layton’s wonderful Choir of Trinity College, Cambridge.

This year saw another closely contested fight with big names like Kaufmann and Perahia slugging it out against relative newcomers. In a nail-biting finale, four discs tied for first place, necessitating a tie break. In the end, the prize went to youth and brilliance, a thorny composer for some, and an independent label that has been a standard bearer for many decades.

The 25 finalists this year were spread across 13 labels with slightly fewer boutique recordings than last year. Repertoire spanned the 16th century to the present, though there was only one disc of contemporary music in the final 25 (as opposed to three in 2016).

So which recordings did our critical panel consider the most outstanding on disc in 2017, and who ended up carrying off the top award? Read on…

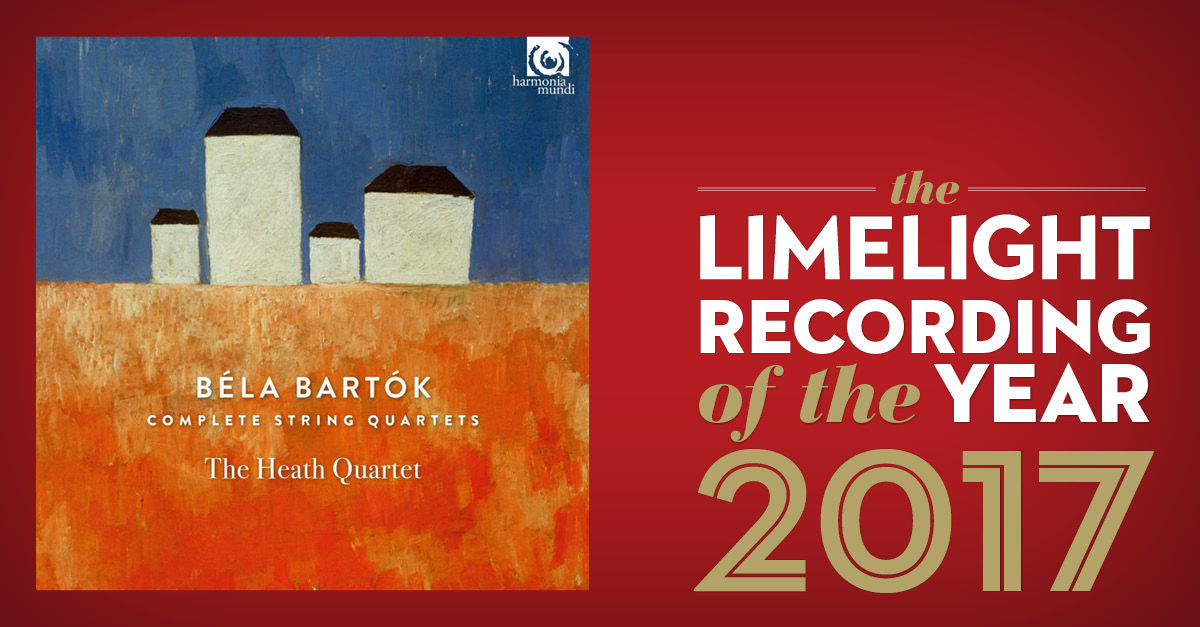

Bartók

String Quartets

The Heath Quartet

Harmonia Mundi HMM9076162 (2CD)

“This is a set to treasure. For newcomers, it’s an ideal way in to works that are admittedly hard to get your head around; for the converted, a refreshing alternative that will have you marvelling anew at the invention of a haunted genius.”

Warwick Arnold, Limelight, September 2017

Read our interview with Oliver Heath here.

Bartók: A life in six parts

The First Quartet is full of this kind of adolescent, yearning, unrequited love. It’s all heart on sleeve, but there are signs in there of what’s to come. It’s his first string quartet but it’s so accomplished and it has such a brilliant arc. And then the Second bridges the gap between the First and the Third beautifully. It has a kind of exoticism and that slightly yearning quality that’s there in the first, but also you can feel that there’s this more abrasive energy under the surface. I think the Third is the most Modernist – it’s the least popular with audiences in a way. It’s pretty uncompromising, and brutal, and it’s the most exhausting to play, even though it’s by far the shortest, because it’s just so intense. The Fourth is very elusive, but I think it is one of his most sublime things. It’s so not of this world. The Fifth is the big one – it reminds me of Beethoven Op. 131. It has that kind of breadth and a sense of ambition, creating something that’s a huge statement. The Fifth is the most challenging technically. The last movement is the scariest to play, but it’s my personal favourite. And I think the slow passages in the second and fourth movements of number Five share the night music quality of the slow movement of number Four. Those two have symmetry in the five-movement shape. Both of them climax in the middle of the third movement, which sounds like quite an academic idea, but when you’re performing it’s amazing to have that architecture in your mind. The Fifth is like a contemplation of death, I always think. The fourth movement is just the most heart-breaking music. The Sixth is the most affective to audiences. It feels very, very personal. The faster sections in the first and third movements feel quite sardonic – well I guess fascism was looming and the Nazis were looming and he was having to emigrate. All the ugliness of humanity is there in spades. Oliver Heath, First Violin in the Heath Quartet

Comments

Log in to join the conversation.