Introducing a new “in-depth” series of articles about the arts and related issues, written by academics and art-makers, Limelight begins with a piece by James Humberstone, Senior Lecturer at the Sydney Conservatorium of Music, The University of Sydney, about his decision to pursue a career as an academic composer, and his new song cycle The Weight of Light, which will be performed at the Sydney Con on Friday July 27.

James Humberstone. Photographs courtesy of the Sydney Conservatorium of Music

Why be a composer in a university?

It was my ambition from my own undergrad days to become an academic-composer. I remember my father posting me a newspaper cutting about how fewer than 1 percent of composers actually made a living just from writing. Once you took the Andrew Lloyd Webbers and John Williamses off the list there was one British art music composer left – Peter Maxwell Davies – and of course, it hadn’t always been that way for him, either.

So my ambition was born not of any altruistic sense of wanting to help foster the next generation of composers, or to help innovate and extend the offerings of a tertiary institution, but because I wanted to write the music that I wanted to write, and this was the most reliable way to be paid, at least in part, for doing just that.

For those who don’t know – and this is different in every country and ever-changing here – for us composers, our musical output is considered our academic research (or, to be more precise, “Non-Traditional Research Output”). That doesn’t just mean that you can simply write a tune every week or two and call it research, though. There are a bunch of metrics any work needs to measure up to, essentially to show that it’s doing what traditional research does – adding to the knowledge of humankind. We need to show that our music is exploring new ideas, and that it has impact (performed in a major venue, and/or by significant performers; the score or recording published commercially; national press reviews, and so on). The “publish or perish” saying is just as true for a composer as it is for a scientist, if you’re working in a university.

The circuitous route

Despite knowing early on that I wanted to be an academic-composer, it took me nearly two decades to complete the training required, unlike many friends who completed their PhD within years of undergraduate study. I had familial responsibilities, and worked full-time, while studying part-time for two masters degrees (one in composition, and then a second in teaching) and then a PhD.

That circuitious route turned out to be extremely good for me, though. Doing some fill-in secondary school composition teaching, I discovered that I adored teaching, and working with young people. Once in a more permanent role in a school, there were commissions to write for the children, and while I was, for a while, worried about being labelled as a school-music-composer, there was so much to learn compositionally if you were to produce effective work for children’s musical limitations.

And so my aesthetic as a British post-experimentalist broadened to become a post-Cardewian Anglo-Australian composer for schools, community ensembles, and new music groups, identifying with those who had worked across similar lines – Britten, Holst, J. S. Bach, and so on. Good company. I also worked for nearly a decade in music technology, doing everything from tech support to helping design new features of software for composers and educators, and was soon invited to speak around the world about how technology could be used meaningfully in music education.

And so, when my circuitous route to a PhD was completed in my late thirties, I did not have a huge catalogue of published scores or traditional research, but I did have a huge range of works performed all over the world by players from four years to – well, older than four years; had written pretty much entirely to paid commission for a decade, I’d written text books, taught in a number of school systems, taught casually in tertiary institutions, had working relationships with many in the music technology industry, had several theses ready for conversion/expansion to publication, and was already a keynote speaker on the circuit. In fact, while my PhD was with the markers, a rare job opening became available at the Sydney Conservatorium of Music, lecturing in music education, and I was lucky enough to snap it up.

Footballers have 4-4-2, we have 40-40-20

At my university, and at many others, academics work a 40-40-20 load. This means that 40 percent of your time is spent teaching (and associated duties, such as marking, meeting with students, and supervising postgraduates), 40 percent of your time is spent doing research, and 20 percent of your time is for “service”, which ranges from sitting on committees to getting out into the community and helping out in your field.

Of course, in reality, the teaching bit takes up much more than 40 percent of your time, especially if you love it as much as I do (OK, apart from the marking) and want to continuously improve your practice, rewrite your content, and so on. Unlike school teachers, academics get the same four weeks a year leave as the average full time Australian employee, though we do have the advantage of being able to work wherever we like out of semester if we don’t have other responsibilities (those committees).

And maintaining a minimum research output is no mean feat, especially if you’re working on large scale works which may not be premiered for several years. The stress of having to maintain this “proveable” output has worked against many composers. I want to make the point that it isn’t a cushy job before I tell you why it’s an amazing job. I remember Matthew Hindson telling me, just before I applied for the position: “you’ll work harder, have fewer holidays, and for less money. But you’ll work with the best people, and have unending opportunities”.

He was right.

My output since 2013

Since taking the post at the Sydney “Con”, I’ve been able to work on the projects I want to, to really freely explore my art and also try to do useful and impactful things with it. This was what I always dreamed of. Projects included an intimate percussion work, Campanella, for Synergy and the ABC; a number of large scale works for massed children or community ensembles; my first electro-acoustic work for years, Noise Husbandry, which is an interactive installation onboard the destroyer and submarine at the Australian National Maritime Museum on Sydney’s Darling Harbour; and an (ongoing) cross-arts work for orchestra, choir, cinematopgraphy, spoken word poetry, and hip-hop, Odysseus : Live with MC Luka Lesson.

Odysseus is a re-telling of Homer’s Odyssey, and draws parallels with current troubles in the middle east, and the plight of refugees. I’m currently working on the third version of it, supported by Arts Council funding. And it’s a great example of being able to work on something that really is important – breaking new ground musically, and engaging with a topic that is difficult to explore, which is of course why we need art. At the same time, I’ve spent four years working on another project of equal importance and impact, The Weight of Light.

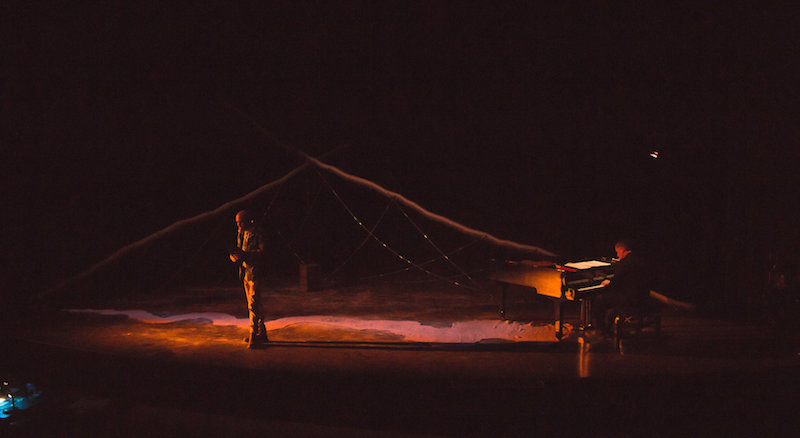

Michael Lampard and Alan Hicks in The Weight of Light.

Michael Lampard and Alan Hicks in The Weight of Light.

The background to The Weight of Light

I have worked with Paul Scott-Williams, director of the Goulburn Regional Conservatorium (GRC), for the best part of two decades – he’s most definitely a close friend as well as a colleague, artistic collaborator, and an inspirational leader. We met at a Soundhouse conference in Lorne on the south coast of Victoria in 1999, and I was struck (as were others, I think, and those who I’ve seen him work with before) by his balance of warmth and ferociously high standards. Paul engaged me for two residencies at his institution soon after, where I wrote pieces for differing age groups and ensembles of instrumentalists, singers, and integrated music technology. I learned so much from him, and he seemed to think my work was good, which I took as a huge compliment given the incredible standard of his own work.

After Paul took the position at the GRC around the start of this decade, he asked me to compose a work for his friend, the brilliant Michael Kieran Harvey. And just as I was platting what fiendishly difficult music I could challenge Michael with, Paul mentioned that it was also to act as an outreach project with his feeder primary schools. In a common haze of cognitive dissonance brought on by someone who can conceive of a project like that, I eventually came up with a three part plan: (1) a children’s book about some children who prefer living in their own imaginations than in the “real world”, but connect the two by playing and improvising/composing for the piano; (2) A series of compositions that could be both concert music for Michael to premiere, but also would follow the narrative of the story; and (3) three simplified versions of those compositions for the feeder schools to improvise and perform with.

That work was terrifically meaningful to me, and thanks to the success of the eBook (which was rated in the top 10 of the iTunes bookstore for several years!) it had a life outside Goulburn. Every few months Paul and I would be in touch, and we would discuss what the next “world-changing” project might be. Then one day he rang me up and told me it was going to be a song cycle. Proper Art Song, he said, that would push the boundries of the form while identifying strongly with it, and establish a fresh path for contemporary song cycles in Australia. That he has met a brilliant writer called Nigel Featherstone, a Goulburn local, and he had agreed to write the libretto. That the work needed to address issues in the Goulburn centring around masculinity, and that he would premiere it.

Working with Nigel Featherstone

I headed down to Goulburn soon after to meet Nigel, which I did over dinner and a bottle of wine or three at Paul’s house. We talked a little about the threads that Paul was interested in exploring, but the great benefit of that meeting was seeing that (as I might have expected) Paul had chosen in Nigel a writer who was articulate, considered, incredibly clever but not aloof, but most of all – warm. We also seemed to share similar ethical and political compasses, which in a work like this would help, although at no point did it become a driver for the work, as one of our reviewers pointed out.

Nigel was also passionate and incredibly knowledgable about music, which was a double-edged sword for me. First, I wanted him to like the music that I was going to set his words to, and it was great that he knew so much about music, and the music he liked, and had ideas about what might and might not work with his words, because he brought that to the process. Second, I wanted him to like the music that I was going to set his words to, so it was terrible that he knew so much about music and had the skills to judge what I was going to do!

We had lots of meetings after that. Regularly by email. Some in Goulburn, and one at the Con in Sydney, which Nigel seemed to get a real kick out of, and in turn which reminded me how lucky I am to work there. Nigel sent a first draft libretto. I started working. Eventually I struggled my way through the first few sketches of a few songs in a practice room at the GRC. Nigel didn’t seem to hate it. In fact, he seemed to like some of them. And where he didn’t … I got the feeling he was opening to hearing more and finding our what I was trying to do. From then on, the collaboration was easy for me – fun, respectful, and incredibly fruitful.

But setting the text wasn’t.

The Weight of Light

The Weight of Light

Nigel’s libretto for The Weight of Light

The story is dark, and the text is dark (in fact, there’s lots of light/dark metaphor throughout, but in this case, I just mean plain dark). Imagine being a soldier, a Good Man, perhaps a Hero in the eyes of some, but knowing that through your gunsight you had killed an innocent little girl.

A feeling of falling

in my chest

my guts

my legs

my head

Imagine, having spent your lifetime as the protectice Tough Big Brother, returning home after three months away to find out your little brother can’t handle it without you, and has taken his own life.

We’ve lost him, he’s gone,

he went in winter –

by his own dear hand

he slept himself away

to heal his own dear heart

And imagine that in the middle of this you find our that a careless night in the sack on your last trip home has resulted in another coming surprise.

And now her eyes

widen and redden:

I’m pregnant, she says,

the baby’s yours

As a composer, setting a text usually gives you a head start on the creative process. For a start, text has rhythm, so while you might play around with it, and not always set it completely naturally, it certainly dictates much of the rhythm in the vocal material (in fact, the text can be difficult to understand if it’s not set with its natural emphases, and so it would be somewhat insulting to the librettist to deliberately “break” it). Second, unless you’re setting Cage or perhaps Beckett, the text has narrative and/or emotion and even without those it will. almost definitely provoke imagery. You can seek to contradict those elements in the music, which can add another layer to the narrative itself, but again, it might not be a respectful or even plain senseible way to treat the text. So, as a general rule, as well as influencing (if not dictating) the rhythm of the vocal material, the text is influencing (if not dictating) the mood of the work, which in turn influences the musical language that one adopts. That’s the head start I’m talking about – the power that the text already has over the music that you’re going to write means that you can just take a few things as given and get on with it.

However, that wasn’t entirely true in this case. Of the 14 songs, there wasn’t one that was obviously “upbeat”, although some were emotionally lighter than others. But most were dark – and there we are back at that word again. Beautiful, ugly, and difficult words about difficult life events. I had to treat them in a way that supported the narrative, but I couldn’t write 14 songs of darkness – there wouldn’t be the contrast required to engage an audience in an hour-long work, and it would just be plain, well, depressing.

So I analysed the text. Over the best part of a year, if I couldn’t get a few clear days to write, I’d analyse the words. Reading them again and again allowed me to find themes in the text, and plan how those themes might work in the music. I realised that structurally the piece needed space, and so I planned little “lacunas” where the piano could allow the strory to set in, and the emotion to pass through the room and the listeners, to alleviate the moments where we would bombard them with it. The more I read, the more beautiful I found this dark dark text, and the more I loved it.

as the rain comes down on the iron

you and I

we’ll be a rock

a boulder

a flooded river flowing

a bird riding a wild, wild wind

And the composition became easier, apart from when, between the first public workshop in June 2017 and the premiere in March 2018, Nigel decided to withdraw three songs and write three new ones! But over the four years we created the work, the collaboration was just wonderful, and that cames down to two things – Nigel’s (and Paul’s) warmth, and the brilliant, impactful and emotional words that he wrote.

The Weight of Light will be performed at the Sydney Conservatorium of Music, with baritone Michael Lampard and pianist Alan Hicks, on July 27 at 1pm and 7pm

Comments

Log in to join the conversation.