Robertson shows a deep understanding of Wagner, but opera stars fall short of expectations.

Concert Hall, Sydney Symphony Orchestra

20 June, 2015

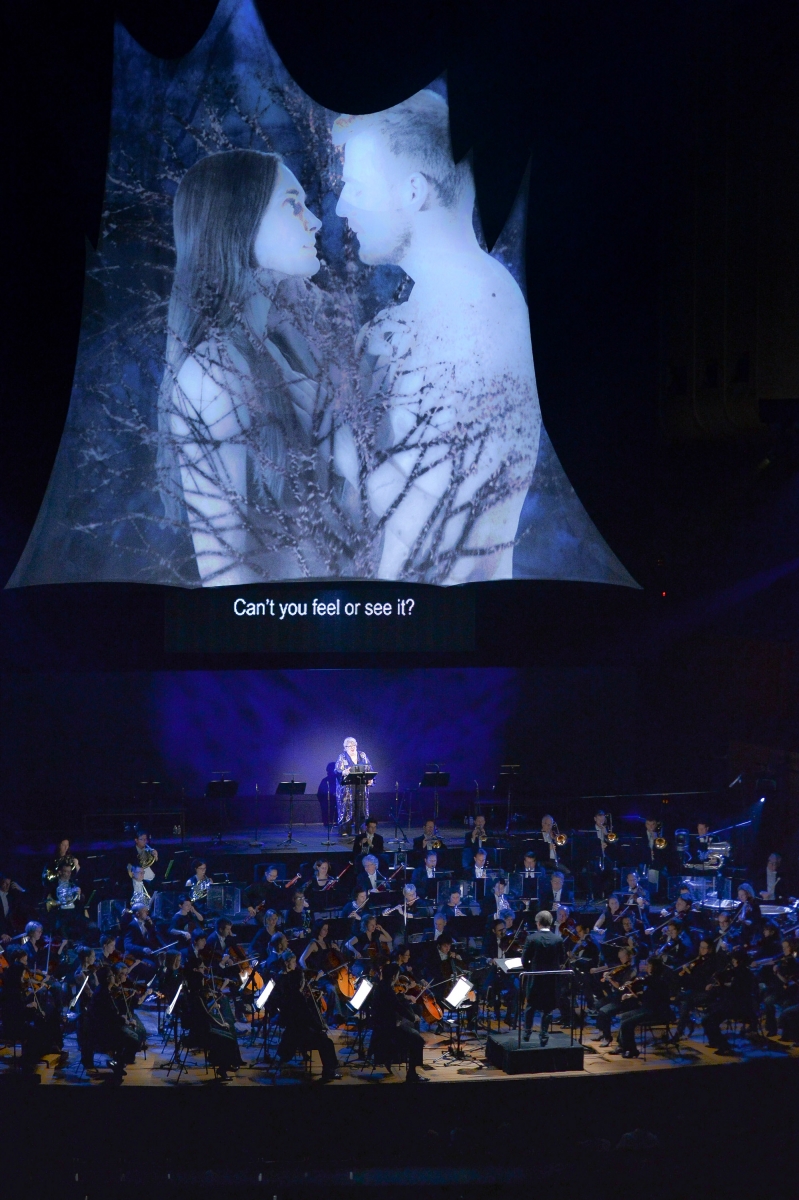

Where Wagnerian opera is concerned, size is everything, but it’s not just the scope of the gargantuan orchestral forces, brawny, ironclad voices, and herculean stamina required for his epic operas that’s big. The philosophical and emotional exploration at the heart of these stage works is on a cosmic scale, and justifiably craves an equally sizeable backdrop to effectively communicate. It’s little wonder therefore that Wagner’s operas rarely have an outing on the diminutive stages of the Sydney Opera House, and indeed it’s been eight years since Sydneysiders have had the chance to see one of the composer’s music dramas, fully staged, on home turf. However the Sydney Symphony Orchestra’s magnificent concert presentation of Tristan und Isolde is an admirable – if not completely flawless – demonstration of how to deliver the titanic power and drama of Wagner when space is in short supply.

With virtually every inch of the concert platform occupied, not forgetting the auxiliary ensembles, off-stage players and male chorus shoehorned-in around the Concert Hall’s auditorium, SSO Chief Conductor David Robertson showed masterful control over the army of musicians at his command. This was a highly sophisticated account, richly sonorous and contoured. The orchestra were nimbly responsive to Robertson, with barely a dip in concentration or accuracy throughout the marathon 5-hour performance. For Bayreuth purists Robertson’s pacing is perhaps a bit too fleet, particularly in the dark, despairing moans of the strings at the opening of Act III. However his sense of dramatic tension is so consummate, his ability to annunciate the narrative thrust of Wagner’s enigmatically chromatic music so coherent, that this swifter flow felt perfectly judged.

Throughout, the performance bristled with the ingenuity of Wagner’s score, translating the irreconcilable conflict of desperate, inconsolable desire and inevitable oblivion into music. Robertson’s understanding of this dramatic tension was clear, and his emphasise of Wagner’s persistently unresolved harmony only served to heighten the celestial power of the final cadence, signalling the corporeal release of the two lovers.

Of course it’s one thing to draw an audience persuasively into the tragic, yearning world of Tristan and Isolde within the theatrical arena of a darkened opera house, and quite another to do it in the less engrossing environment of the concert hall. This performance managed to overcome this hurdle in most respects, with only a few obvious handicaps remaining.

In comparison to the legions of instrumentalists and chorus members, out on display and not shuttered away in a pit, the eight soloists felt at times rather outnumbered, and placed on a platform behind the orchestra – a necessity through lack of room more than anything else – the task to overcome the orchestral palette was occasionally a struggle.

(Photo: Ken Butti)

(Photo: Ken Butti)

Soprano Christine Brewer’s Isolde was the most conspicuously overwhelmed, and during the mammoth duet in Act 2 the effort was especially evident in her upper register. However, when not in competition with the full orchestral juggernaut, Brewer offered a beautiful nuanced and expertly controlled tone.

By contrast Canadian tenor Lance Ryan’s Tristan was all strength and power, but this veered too often from mere projection into a brute-force bludgeoning, exchanging a more pleasing colour for a flat, vibrato-free shout.

However, where Ryan and Brewer may have disappointed, the supporting cast truly surpassed expectations. Former Cardiff Singer of the World winner, Katarina Karnéus, who stunned audiences last week with her performance of Berlioz’s Nuit d’ete with the SSO, was equally impressive in this concert as Isolde’s companion Brangäne. Her full-bodied, sweet, mellifluous mezzo was deeply expressive and entirely moreish. The thick, reedy, elemental bass of John Relyea as King Marke was a potent display of regal might, and Boaz Daniel the faithful squire Kurnwenal provided a pleasantly buoyant foil for Ryan’s frail, injured Tristan. John Tessier’s dual role of the Young Sailor and Shepherd was also a surprise highlight, executing both parts with a clarion-clear timbre and beautiful, lighter-than-air effortlessness.

Some creatively conceived projections, by New York-based artist S Katy Tucker, provided some theatrical stimulus to the sterility of the concert hall. Tempestuous, turbulent, dreamlike scenes gave us sensuous glimpses of the young lovers, moving ethereally in super-slow-mo, but diluted the dangerous intensity of this relationship’s chemistry. Sadly, on stage Ryan and Brewer’s performance was largely inert and disappointingly static. The addition of carefully choreographed lighting offered a further gesture of some dramatic context, it couldn’t quite compete with the full, crushing impact of this mortal drama when experienced in the more viscerally charged space of the opera stage.

Comments

Log in to join the conversation.