★★★★☆ Paul Capsis captures the infamous raconteur Quentin Crisp with forensic precision.

Fortyfivedownstairs, Melbourne

May 26, 2016

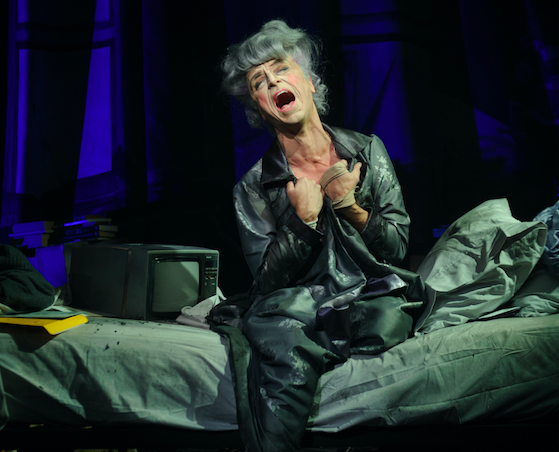

In the gloaming light of a dilapidated hovel, a wizened, desiccated figured in a filthy bathrobe sits on a stained mattress. His features are shrivelled and drawn; angular bones stretched over with skin the texture of week-old fish. Untamed hair clings to this haggard character’s head, both its colour and spurious volume announcing its synthetic origins. Dirty bandages wind their way around bony limbs and clawed hands; death can’t be far away. It’s a hopeless scene, bleak, toxic and utterly repulsive.

This could be the set up for a Beckett-ian dystopia, but remarkably, this is art imitating life, specifically that of infamous queer raconteur Quentin Crisp. He was a character so complex and colourful, that his existence seemed to be played out in endless contradictions. Known for his florid styling, foppish wardrobe and acidic critique on the human condition, his effeminate fashions and aristocratic vocabulary masked the pigpen poverty of his home life. In Tim Fountain’s Crisp biopic, Resident Alien, we meet him in 1999, aged 90, possibly in the final days of his life. Living in a bedsit in the last rooming house in New York, his existence is at the polar extremity of his extravagant reputation, and yet despite the myriad limitations this suggests – financial, physical and social – his most prized possession, his intransigent mind, remains defiantly sharp.

Until his last breath, Crisp’s ideologies refused to concede even the smallest amount of vulnerability. He may have lived in a health hazard of a dump, but this was entirely by choice. As he points out in quintessentially flippant fashion: “There is no need for any housework at all. After the first four years, the dirt doesn’t get any worse.”

Crisp was a one-off. An anti-hero, philosopher, icon and scoundrel, who was hated for what he said but loved for the way he said it. Capturing his essence without stumbling into full-blown caricature requires an actor with a unique equilibrium of empathy and detachment, and I doubt there is another performer in the whole of Australia capable of achieving this, with such a fine-tuned level of forensic precision, as Paul Capsis.

Capsis is no stranger to camp, but Crisp calls for a very specific spectrum of characteristics, which could arguably pose a greater challenge for Capsis than most. The high-voltage showmanship we expect from this cabaret star has to be smothered under Crisp’s decaying physicality. Capsis’s innate punk-spirit has to give way to Crisp’s deliberate and ostentatious delivery. Superficially, Capsis and Crisp might appear to fall from the same tree, but these are two very different fruits.

Perhaps the most arduous element of this role is how little personal input is permissible. The voice, mannerisms, gait and affectations of Crisp are heavily documented, and so achieving an authentic performance is a matter of absorption rather than characterisation. The challenge of assimilating such a large amount of information, while still bringing something personal to this role, is nothing short of herculean, and Capsis achieves this almost without faltering. Occasionally you can see the cogs turning before an entry, and these momentary breaks in character were fairly conspicuous on opening night, although this is surely something that will settle as the run continues. Regardless of these minor trips, Capsis delivers a truly astonishing account, well-realised at every level from the grandest flourish to the smallest detail.

Director Gary Abrahams has made some bold choices with his treatment of this text, and for the most part, these gambles pay off. As a 70 minute monologue with almost no dynamic action, there is, of course, a risk of stagnation. Equally, too many embellishments and inauthentic accents can shove this piece into the realm of pantomime. Abrahams has opted for a more stylised aesthetic. The level of decay in Romanie Harper’s sets and costumes are warped just beyond the naturalistic and Rob Sowinski’s lighting heightens the emotional perspective without the need for superfluous physicality on stage.

For me, Abrahams’ master stroke is allowing Crisp’s fragility to be so visible, tingeing certain eccentricities with a raw honesty. Answering the phone to any and all callers is transformed from a brazen display of fearlessness into a quietly desperate lifeline from total isolation. When two expected guests, Mr Brown and Mr Black, cancel their appointment, a subtle yet penetrating note of disappointment betrays the scale of this letdown. Certain passages are allowed to swell from Crisp’s trademark indifference towards a more exaggerated emotion range. Preaching at us with a frustrated yawp, it suddenly becomes clear: his rolling commentary on the world isn’t motivated by pretentious disapproval but by profound personal regret. Of course, much of this play is extremely funny, as you might expect of a text constructed entirely from a wit as bone dry as Crisp’s, but it’s these flashes of touching frailty that reveal the most impressive feats of this production.

Cameron Lukey presents Paul Capsis in Resident Alien at Fortyfivedownstairs, until June 12.

Comments

Log in to join the conversation.