The colonial histories of South Africa and Australia have much in common. Issues of land, cultural collision and how today chooses to look at the events of the past are hot topics in both societies. So like the blistering Transvaal-located Mies Julie that came to Perth International Arts Festival two years ago, Gregory Maqoma’s potent one man dance performance Exit/Exist has special resonances that cannot fail to go unnoticed.

Soweto-born Maqoma began formal training in 1990, but cites Michael Jackson and 1980s pop culture alongside traditional Xhosa, Zulu and Basotho dances as formative influences. Founding Vuyani Dance Theatre in 1999, he’s since worked with Akram Khan and other practitioners at the fissile coalface of dance theatre, and nowadays describes his unique choreographic style as a “cocktail of genres, traditions and histories”.

Maqoma describes Exit/Exist as “rewinding the tape”, and a sense of time – from clock projections to sand pouring through an hourglass – is critical to his excavation of the life of one of his ancestors. The 19th-century Xhosa leader of the same name lead a guerrilla campaign against the British colonial invasion in 1837. Eventually captured and imprisoned on the infamous Robben Island, Chief Maqoma died there in 1873 in what are described as “mysterious circumstances.”

An arresting opening reveals Maqoma, back towards us, in a dazzling golden suit, his fingers fluttering as if exploring an invisible string instrument. Music loops underneath and Maqoma’s legs (a show all of their own) seem to take on their own life. A loose-limbed, swivel-hipped solo throbs with a palpable mounting energy and the pure joy of dance. This is the here and now, he seems to say. A pause sees the modern Maqoma undress before events duly rewind and he’s ritually robed as the Xhosa Chief.

The dance may be a one-man affair, but Exit/Exist comes with a glorious score as willing co-partner. Simphiwe Dana’s laid-back ambient tracks run seamlessly into Italian-born Giuliano Modarelli’s atmospheric and skilfully executed guitar solos, the composer/musician frequently glimpsed behind a gauze at the back. A haunting quartet of singers – the superbly disciplined Xolisile Bongwana, Anele Ndebele, Sizwe Nhlapo and Siphiwe Nkabinde – take part in the action as well, moving things around the stage and bringing focus at moments of heightened emotion. Their powerful vocals to Xhosa texts are a blend of traditional harmonies (and those ululating bursts that are peculiarly African and send shivers up the spine), with a more urban, contemporary groove.

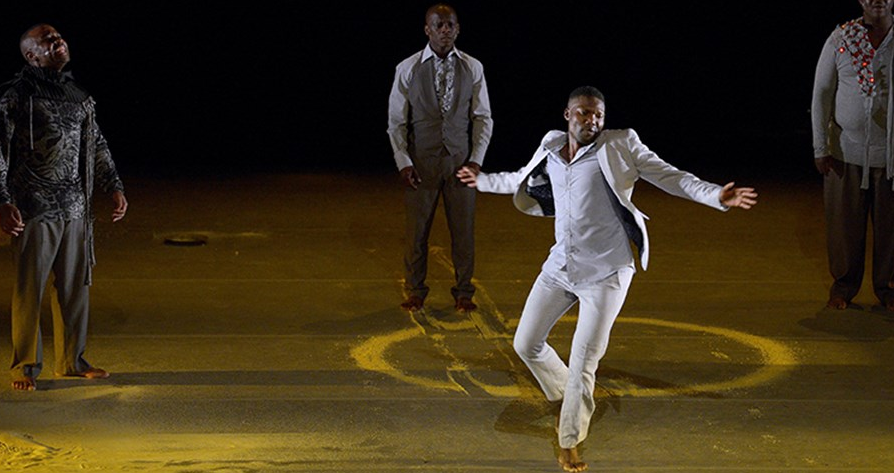

As the work progresses we see the figure of the proud Maqoma in a sequence of dances reflecting aspects of his story – the conflict with the British over land and cattle, negotiation, interrogation, imprisonment, and a range of rituals evoking the spirit of 19th-century South Africa. The approach is abstract – at times frustratingly so – though the dance, laced with the stamping, strutting feel of traditional movement is always compelling. Simple props – cattle horns, a silver dish, two mounds of golden earth and a bowl of water – help guide us through the story, though those looking for a tangible narrative may be disappointed.

Gregory Maqoma visited the Eastern Cape to study traditions and ritual in the villages where his ancestor lived, but also, he says, “to run and breathe on the land that Maqoma ruled”. He even visited the Chief’s grave to ask a blessing of his spirit. That sense of authenticity and respect becomes increasingly evident as the dancer confronts a rising tide of frustration and despair.

The final moments are harrowing. Drenched in sweat, Maqoma quivers, every gobbet of flesh and muscle spasming as he inhabits the indignity of his ancestor’s imprisonment and lonely end. Palsied limbs reached out pouring oil over a wracked torso, as if the dying man as sole witness is responsible for his own ritual anointing. It’s brave, confronting theatre, and almost too painful to watch.

Though it seems a million miles from the joyous opening, nevertheless there’s a return of sorts as Maqoma dresses and drags us back to the present. This time, though, any sense of celebration is undercut by our awareness of the past and of man’s inhumanity to man.

Land continues to be an issue in South Africa, as it is in Australia. The overthrow of Apartheid hasn’t substantially closed the gap between the rich and the poor, just as Kevin Rudd’s apology, nine years on, hasn’t poured wealth into Indigenous Australian outback communities. I’d like to think the standing ovation that greeted Exit/Exist didn’t just acknowledge Maqoma’s 60-minute tour de force.

Comments

Log in to join the conversation.