Moscow. January 1868. The Great Hall of the Nobles. Hector Berlioz conducts triumphant performances of Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony, as well as his own Symphonie Fantastique and Harold in Italy, the quasi-symphonic viola concerto based on Byron’s Childe Harold. Although no more than “a little white bird with pince-nez,” according to Rimsky-Korsakov who was there, the Russians took the desiccated Berlioz and his wild music to their hearts. Mily Balakirev prepared the chorus for the concerts, and at the banquet afterwards, a 27-year-old Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky gave the toast.

Around the same time, the influential critic Vladimir Stasov had pressed a fleshed out scenario for a four-movement symphony on Byron’s gloomy Manfred upon a dubious Balakirev. A depressive, Faustian magician seeking absolution for some mysterious transgression didn’t chime with the 30-year-old Russian, so that November he sent it on to Berlioz. Alas, five months later the worn out Frenchman, whose programmatic music had been endlessly misunderstood in his own country, was dead.

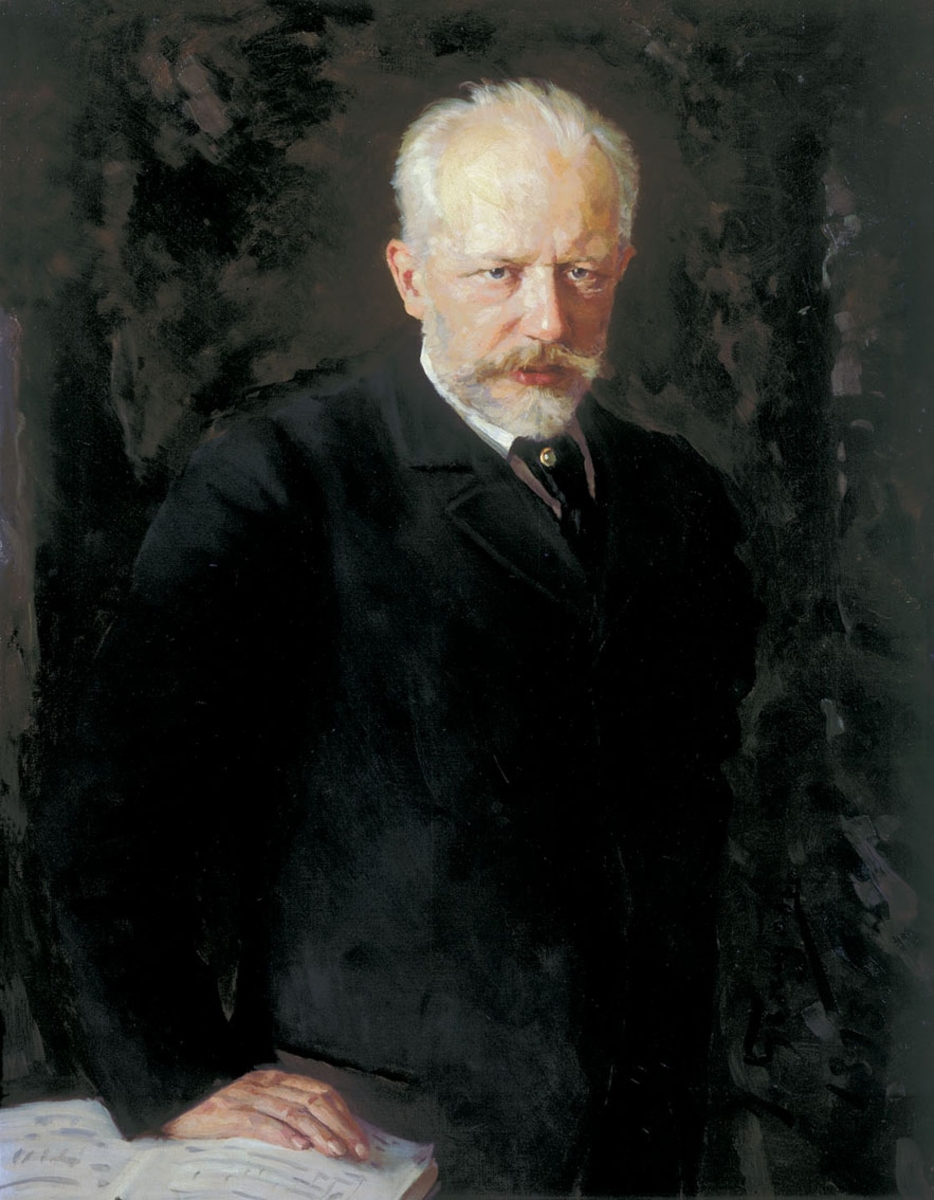

Portrait of Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky by Nikolai Kuznetsov.

Portrait of Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky by Nikolai Kuznetsov.

Fast forward 12 years. Balakirev, suffering from the intermittent creative block that would afflict his career for decades, sent Stasov’s Manfred outline to...

Comments

Log in to join the conversation.