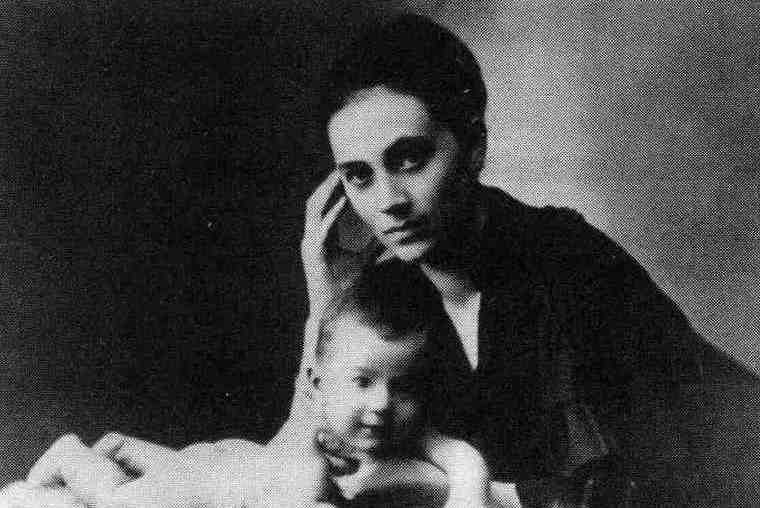

Alma Mahler to Gustav Mahler

“Last December 13th, there appeared in the newspapers the juiciest, spiciest, raciest obituary that has ever been my pleasure to read,” joked Tom Lehrer in 1965 as an introduction to his satirical song Alma.

Not just the inspiration behind several of Gustav Mahler’s symphonies, Alma Mahler-Werfel (née Schindler) was the ultimate groupie of the 20th century’s European artistic elite, serving as muse to visionary men in many creative fields. When Mahler first met her, she was already a renowned beauty in Viennese intellectual circles, with the painter Klimt wrapped around her little finger and an affair underway with her composition teacher Alexander von Zemlinsky. In 1902 she married Mahler, 20 years her senior, at his behest abandoning her own early efforts as a composer of lieder.

The Adagietto of Mahler’s Fifth Symphony is dedicated to his young wife in what friends and contemporaries described as a “declaration of love”. The Sixth may be subtitled Tragische but, ironically, his most pessimistic symphony was composed in 1903-4 during a period of relative domestic bliss and features a soaring melody widely known as the “Alma theme”. He also dedicated the Eighth Symphony of a Thousand to his wife.

In 1910, Alma’s affair with the architect Walter Gropius wrenched from Mahler some of his most anguished musical outpourings. The manuscript of his Tenth, unfinished, symphony is littered with annotations of broken-hearted utterances: “Why hast Thou forsaken me?” … “To live for you! To die for you!” He was so devastated that he booked a day-long session on Sigmund Freud’s couch. The good doctor initially forgot to charge his fee and sent the bill the following year, somewhat tactlessly, to the widowed Alma a few weeks after her husband had died.

Peter Pears to Benjamin Britten

Tenor Peter Pears’ association with composer Benjamin Britten spanned more than three decades and became one of the most fruitful partnerships in the history of British music. Pears was Britten’s lover, muse and chief interpreter in numerous song cycles (Nocturne, the Serenade for Tenor, Horn and Strings) and operatic roles (Peter Grimes, Albert Herring, Peter Quint in The Turn of the Screw and Aschenbach in Death in Venice) created for him. They were also wonderfully attuned to one another in recitals of Romantic music such as Schubert’s Winterreise.

The two met in the 1940s and shared a flat in the United States during WWII. Their voluminous correspondence is touching: Pears often refers to Britten as his “honey bee.” In one letter of 1974, after three decades of sharing their lives, Britten asks Pears: “What have I done to deserve such an artist and man to write for?”. Pears replied, “It is you who have given me everything. I am here as your mouthpiece and I live in your music”.

Upon Britten’s death two years later, the Queen sent a message of condolence to Pears.

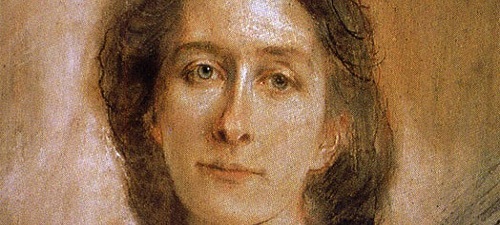

Clara Wieck to Robert Schumann

She was an eight-year-old wunderkind; he was an aspiring composer in his teens who saw her at a concert and so admired her playing that he sought piano lessons from her father. When Clara turned 18, Robert Schumann asked Herr Wieck for his daughter’s hand in marriage, but he was vehemently opposed to the union: so began years of agonising separation and tender correspondence, with many sheets of manuscript exchanged, including some of Schumann’s most affecting Lieder and piano miniatures. He wrote to his yearned-for beloved, “You appear in the Novelletten in every possible circumstance, in every irresistible form… They could only be written by one who knows such eyes as yours and has touched such lips as yours.”

The lovers eventually took Clara’s domineering father to court after he threatened to disinherit her and confiscate her concert earnings. They won love’s battle and were at last married in 1840, the day before her 21st birthday. In celebration of their joyous union, Robert presented his bride with the song cycle Myrthen as a wedding gift – a bouquet or “myrtle of flowers”. He also gave her a marriage diary, in which the couple wrote regular entries for four years (often about their sex life). They settled into a routine: while Robert spent most of his time composing, Clara managed to give concerts and compose a thing or two herself in between running the household and wrangling eight children.

Clara Wieck to Johannes Brahms

One of the most frustrated love triangles in Romantic music was formed when Clara began to champion the music of the young composer Johannes Brahms – like her, a piano phenomenon. He quickly became a great friend of the Schumann family. When Robert’s mental health deteriorated, leading to his institutionalisation and untimely death in 1856, Brahms moved in with his older mentor Clara to help look after her children while she coped with the loss of her husband. Although it is not clear whether they consummated their relationship, in 1855 the 21-year-old Brahms wrote to Clara a frank admission of his feelings: “I can do nothing but think of you… What have you done to me? Can’t you remove the spell you have cast over me?” The two eventually parted ways but remained firm friends.

Countess Josephine von Brunsvik To Ludwig van Beethoven

Josephine came from an aristocratic family of amateur musicians who lived in a magnificent castle near Budapest. She and her sister Therese were brought to Vienna in 1799 for private piano lessons with Beethoven. His feelings for her are documented in at least 15 love letters penned over a long period. Although she appears to have been attracted to the great composer and moved by his devotion, the surviving correspondence indicates that things never progressed beyond close friendship – family pressure and her suitor’s lack of title and social graces may have had something to do with it.

Josephine married twice: first to the much older Joseph Count Deym, with whom she had four children. When he died in 1804 Beethoven resumed his advances, seeing the young widow far more frequently than decorum permitted. At this most intense period in their relationship, the composer was writing the jubilant finale of his opera Leonore (later revised as Fidelio), a work exalting a virtuous wife and the power of married love. The most tempestuous sonata of his middle period, the Appassionata, was written during this time and dedicated to Josephine’s brother Count Franz von Brunsvik.

By 1810 Josephine had re-married, and her union with Baron von Stackelberg proved an unhappy one.

Beethoven composed the song An die Hoffnung (To Hope) and the piano piece Andante favori as musical declarations of love. He seems to have carried the torch for a long time: it is widely thought that Josephine is the subject of his famous, tormented letter to The Immortal Beloved, written in 1812: “… you know my faithfulness to you, never can another own my heart, never – never – never…”

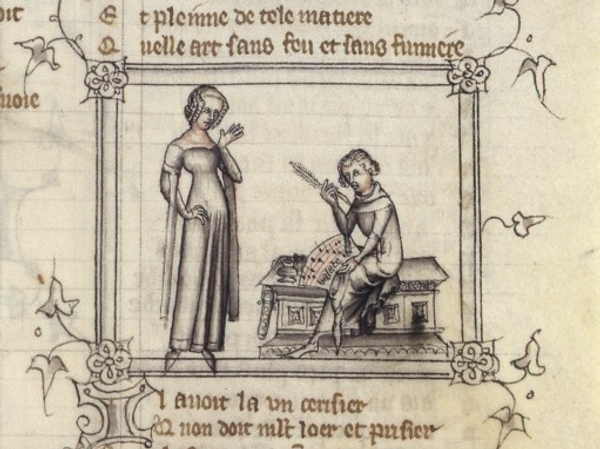

Péronne d’Armentières & Guillaume de Machaut

The most important poet and composer of the 14th century, Guillaume de Machaut (1300-1377) is best known for his Messe de Notre Dame, the first complete surviving setting of the Mass Ordinary. The composer lived through the plague epidemic that swept through the French town of Reims in the 1340s to write some of the most stirring ballades, motets and chansons of his time.

His magnum opus, however, is a sprawling collection of letters, poems and songs written in the name of courtly love. The partly autobiographical, partly fictitious tome Le Voir Dit – “A True Story” (1361-65) comprises 9,094 lines of verse and eight musical settings. In it, the ageing, ill composer is revitalised by the love of a 19-year-old girl who writes to him in praise of his poetry and music. He refers to this young admirer as Toute Belle throughout the poem, in which he eventually meets her and accompanies her on a pilgrimage. In one steamy scene their love is consummated as Venus enfolds them in a cloud. Machaut reveals his lady’s identity only at the end of the poem in the form of an anagram: her name was Péronne d’Armentières.

Kamila Stösslová To Leos Janáček

In the Moravian spa town of Luhacovice, where Leos Janáček holidayed every year, one of 20th-century music’s greatest love stories was born. In 1917, the 63-year-old Czech composer met and fell passionately in love with Kamila Stösslová, a local woman half his age who was married to an antiques dealer. It was Kamila, and not his wife Zdenka, who was responsible for Janácek’s late flowering and the inspiration for the female leads in his operas Kát’a Kabanová (“I always placed your image on K’at’a Kabanova as I was writing the opera; you know that it is your work,” he told her in a letter), The Makropoulos Case and The Cunning Little Vixen. He even envisioned his Glagolitic as a nuptial mass for himself and Kamila, and the 1928 string quartet Love Letters reflects the intensity of their correspondence.

Although it appears the relationship was never consummated, Janácek’s devotion and Kamila’s role as muse is documented in more than 700 letters exchanged over a period of 11 years. In the first of these, in 1917, he asks her to “accept these few roses as a token of my unbounded esteem for you. You are so lovely in character and appearance that in your company one’s spirits are lifted; you breathe warm-heartedness, you look on the world with such kindness that one wants to do only good and pleasant things for you in return.”

Harriet Smithson to Hector Berlioz

In 1827, Berlioz attended a performance of Shakespeare’s Hamlet given by a troupe of British actors at the Odéon Theatre in Paris. There, the 24-year-old composer became infatuated with the Ophelia of the production, an Irishwoman named Harriet Smithson. His obsession grew over the next three years; when in 1830 he heard rumours that the object of his affection was having an affair with her manager, floods of emotion burst forth in the form of a sprawling, programmatic symphony that took the young firebrand only six weeks to compose in the heat of passion.

In Symphonie fantastique Berlioz imagines himself, the lovelorn artist, attempting suicide by opium poisoning. He doesn’t administer a lethal dose as intended, but instead succumbs to a deranged, drug-fuelled dream in which he has killed his beloved and faces execution for the crime.

When Berlioz finally met Harriet in 1832, she was unaware that she had been the inspiration for this grandiose, grisly vision. They were married the following year and produced a son, but the reality was somewhat different to the fantaisie and they separated in 1844.

Cosima Wagner to Richard Wagner

She was the daughter of one colossus of Romantic music, Franz Liszt, and married another: Richard Wagner. Her first husband, conductor Hans von Bülow, was a devoted friend of Wagner’s and a champion of his music, as was Cosima’s father.

In Wagner’s autobiography Mein Leben, he recalls the moment in 1863 when he and Cosima, traveling together in a carriage, realised they were in love:

“We fell silent and all joking ceased. We gazed mutely into each other’s eyes and an intense longing for the fullest avowal of the truth forced us to a confession, requiring no words whatever, or the incommensurable misfortune that weighed upon us. With tears and sobs we sealed a vow to belong to each other alone.”

While still married to von Bülow, Cosima bore two daughters by Wagner: Isolde and Eva. Rumour and speculation abounded but only in 1868, when she fell pregnant with their third child Siegfried, did she demand a divorce from her first husband.

Cosima kept a diary of her daily life with Wagner that reveals her devotion to his music – she often acted as scribe – and their shared vitriolic hatred of Jews. Immediately after her darling Richard’s death in 1883, she sat by the body for 25 hours, refusing to eat for more than four days. Curiously, it was a telegram from her first husband von Bülow that helped her out of her grief: “Soeur, il faut vivre”, it read – “Sister, you must go on living”.

While we are not accustomed to thinking of Wagner as a sensitive romantic, he did get tender-hearted gestures right where his wife was concerned. On Christmas Day of 1870, barely a few months after his wedding and the day after Cosima’s birthday, he arranged for a new composition to be performed by 15 musicians at the foot of their living room stairs, awakening the overjoyed Cosima. This transcendently beautiful “Symphonic Birthday Greeting”, as he called it, became the Siegfried Idyll. “Everything is yours before I write it,” he once told his treasured muse.

Countess Delphina Potocka to Frédéric Chopin

Although Chopin’s best-known muse was his longterm mistress, the French writer George Sand (nom de plume of Amantine Lucile Dupin), he dedicated his Second Piano Concerto and his charming Minute Waltz to a lover he first encountered in his twenties.

The Polish Countess Delphina Potocka was a student of the great pianist. The surviving correspondence between them is racy and frank about their sexual exploits. In a letter of 1833, Chopin described in crude terms the disastrous she was having on his creativity: “Inspiration and ideas only come to me when I have not had a woman in a very long time… Ballads, polonaises, even a whole concerto may have been lost forever up your des durka, I can’t tell you how many. I have been so deeply engulfed in my love for you I have hardly created anything.”

Isabella Colbran to Rossini

In 19th-century Naples, the Teatro San Carlo was considered the most prestigious opera house in Italy, attracting the greatest singers and composers of the day. The company’s prima donna was the Spanish mezzo-soprano Isabella Colbran, a favourite of the theatre’s impresario Domenico Barbaia, with whom the singer was romantically involved. Barbaia engaged Gioachino Rossini, the most famous composer of his time, to pen a series of Neapolitan operas as a vehicle for Colbran’s rich vocal gifts. It didn’t turn out as he planned: Colbran left him for Rossini! But at least the music was fabulous.

In 1815, with Isabella at the peak of her popularity, Rossini composed the title role of Elisabetta, Regina d’Inghilterra especially for his muse. In Otello, Ossia il Moro di Venezia she sang Desdemona. They tied the knot in 1822, and their fruitful musical marriage continued with Armida, Mosè in Egitto, Ricciardo e Zoraide, Ermione, La donna del Iago, Maometto II and Zelmira, all composed by Rossini for his leading lady.

Comments

Log in to join the conversation.